San Francisco is an awesome place to live — we have incredible weather, great job opportunities, and the only two Michelin-starred Thai restaurants in the country (and lots of other great food, but dang). So it comes as no surprise that lots of people want to live here!

And there are lots of reasons to be excited about welcoming new residents. Increasing our population is great for the environment — homes in SF need very little heating or air conditioning, and the city accommodates transit-oriented lifestyles that have low carbon footprints. New neighbors open restaurants and cafes, create art that enriches our lives, grow the tax base, and might even start the next billion dollar company.

With so many people wanting to live here, it follows that we have to build a lot of housing to accommodate them. Unfortunately, San Francisco hasn't allowed enough housing to be built for decades, and shows no sign of stopping.

In a report released in October, a state housing watchdog laid out the scale of the issue:

In order to meet its housing need, San Francisco must add 10,259 units of housing, including 5,825 affordable homes, each year through 2031. [...] according to data published by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, San Francisco permitted just 179 new housing units through the first six months, or 181 days, of 2023 — a rate of less than one unit per day.

If we continue at this pace, it will take 229 years to achieve our 8 year housing goal!

The consequences of under-building are drastic and affect all San Franciscans. When demand outstrips supply, the result is a bidding war for the existing housing stock that drives up rents, pricing out all but the most well-off. Instead of growing the city, we end up driving out the middle class, young families, and people striving to make a better life. This makes SF a less vibrant place to live, locks people out of high paying jobs or forces them to make long commutes, and makes it near impossible to raise children.

Anti-growth activists often say that building new homes only makes developers and landlords rich, but that couldn't be farther from the truth. In fact, major landlords love the housing shortage, as they'll happily explain to journalists and investors. Stagnant housing stock in the face of high demand is a huge opportunity to collect record rents, whereas increases in supply cut into their profits. And academic studies have repeatedly found that building new homes makes a neighborhood more affordable and gives both renters and buyers more high-quality housing options.

Building stuff in San Francisco is really hard

The causes of the housing shortage are straightforward. While there are some factors we cannot control (we're surrounded on three sides by water), there are many that we can control and are currently dropping the ball on.

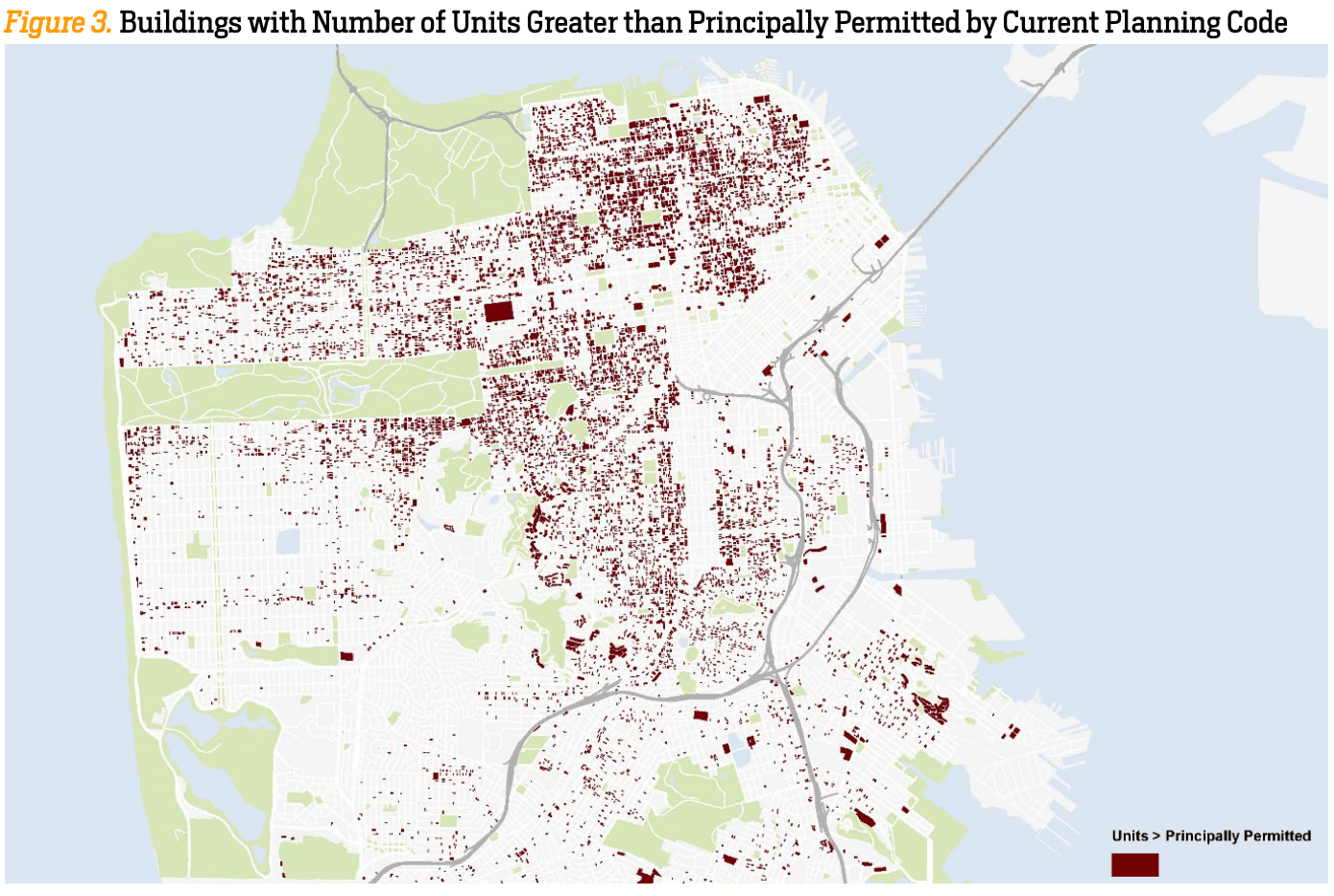

We started dropping the ball, catastrophically, in 1978. In an infamous vote that year, city politicians voted to massively downzone the city. This decision made the most affordable type of homes (multifamily apartment buildings) illegal in the majority of the city. It's worth noting how extreme this measure was — an incredible number of the buildings already in existence by 1978 were in violation of the new zoning laws, and would be illegal to build today. In other words, San Francisco as we know it today could not exist under current zoning laws.

In practice, banning apartment buildings in most of the city reduced the allowed density by a factor of 10 or more — a block that could have previously housed 1000 people can now only house 100. As demand for living in San Francisco continued to rise over the following decades, this decision proved to be devastating for the middle class, which found itself increasingly priced out of the city. Meanwhile, windfall profits were given to the few who were lucky enough to buy land at the right time.

And in those places where new housing is allowed, a maze of complex and unpredictable permitting processes ensures that building is a slow, expensive process. In 2022, it took an average of 523 days for a project to be issued entitlements, and that's before anything is built! On this metric San Francisco is the slowest jurisdiction in California. These entitlements are just one step in getting permission to build something (you also need demolition & construction permits, electrical connection permits, inspections, etc), so the actual timelines for projects extend well beyond 523 days.

And if you manage to make it through this process, your project can still be struck down by the Board of Supervisors, even if you're following all the rules. A high profile example of this in recent years is 469 Stevenson, a project that aimed to replace a parking lot in SOMA with 495 homes, including 73 subsidized homes for the working class. After the project had already been approved by the Planning Commission, the Board of Supervisors revoked this approval, effectively halting the project. And again, 495 homes is more than SF is currently on track to build this year, in one single project.

The Board of Supervisors is far from the only obstructive body — in fact, a single person can stop just about any development in its tracks by filing a CEQA lawsuit. While CEQA is supposed to protect the environment, in this context it does anything but. Stalling construction of apartments in SF forces people to build further out, often in marshes and wetlands, or in fire-prone areas, and then drive hours-long commutes to work.

We can fix this

In recent years, pro-housing movements have seen a huge upswell of interest, and our representatives in city and state government are taking notice. Encouraged by the popular support and compelling logic of housing abundance, a number of housing champions have emerged. State senator Scott Wiener and Assemblymember Buffy Wicks have built a pro-housing coalition in Sacramento that just wrapped up a massively successful 2023 legislative session. The state legislature passed a slate of bills to cut through red tape and fund affordable housing.

Amongst the bills passed in the last year are:

- AB 1633 - stops the abuse of CEQA to block the construction of environmentally beneficial new homes

- SB 423 - cuts red tape around building affordable and mixed-income housing

- AB 976 - expands the freedom of homeowners to build accessory dwelling units (ADUs) on their property.

We need your help

Far from being over, the fight for common sense housing policy is just beginning. The same supervisors who have for years opposed new housing in San Francisco now continue to drag their feet, even as the state puts pressure on them to build.

Fortunately, we're recently made huge strides in electing leaders that share our values, and plan to make many more. Last November Matt Dorsey and Joel Engardio, two pro-housing candidates that we endorsed, won their races for supervisor. And we plan to follow up on this performance in 2024.

Winning a common sense majority on the Board of Supervisors (the city's legislative body) in November 2024 is key to fixing our city. But in order to do that we first need to win races in March for the Democratic County Central Committee (DCCC). This body makes endorsements on behalf of the Democratic Party — endorsements that show up on the ballot and that many San Franciscans depend on to help them make decisions. Unfortunately the DCCC is currently controlled by far left, anti-growth political insiders, who routinely back anti-growth candidates like Connie Chan, Dean Preston, and Aaron Peskin and oppose overwhelmingly popular measures like the school board recall.

Getting a majority on the DCCC would change all of this, in time to make a difference in November. Elections for the DCCC are open to all registered Democrats in San Francisco, so if you haven't already, register as a Democrat in time for March. Look out for our voter guide, in which we'll share our picks for leadership to get us back on track.

2024 is a huge opportunity to choose the future of our city. Whether we continue down our current path of unaffordability, inefficiency, and stagnation, or decide instead for a future of abundance, growth, and affordability, it really does hang in the balance between these two key elections. If 1978 is a year we remember for its disastrous downzoning, let 2024 be the year we look back on in future decades as the year we righted our course. We can do this!

Generate a Personalized Email to the Board of Supervisors

To:

Sign up for the GrowSF Report

Our weekly roundup of news & Insights