Supervisor, District 3: Aaron Peskin

Aaron Peskin

District 3 Supervisor

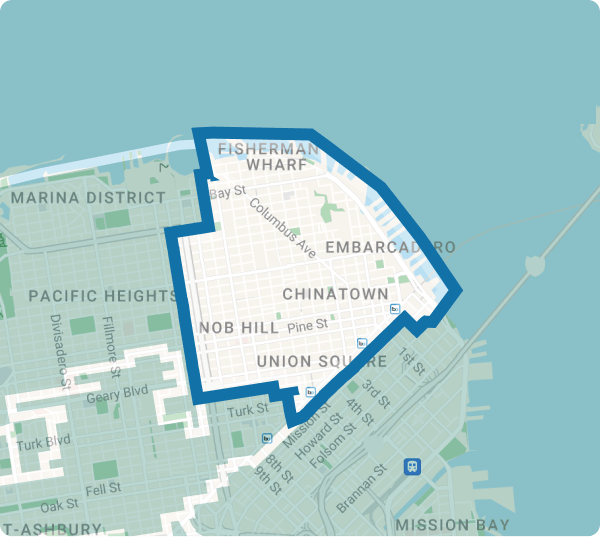

District 3 includes North Beach, Chinatown, Telegraph Hill, North Waterfront, Financial District, Nob Hill, Union Square, Maiden Lane, and part of Russian Hill.

Special Election

November 2015

Won by 1,426 votes.

Elected

November 2016

Won by 11,764 votes.

Re-elected

November 2020

Won by 3,731 votes

Left office

January 2025

This is an archived page. Aaron Peskin is no longer a member of the Board of Supervisors.

Aaron Peskin was the Supervisor for San Francisco's District 3 until the November 5, 2024 election.

Aaron Peskin served five terms representing District 3 on the Board of Supervisors. He was first elected in December 2000 and was re-elected in 2004. He termed out after eight years, as the city's term limits prohibit more than two consecutive terms, but supervisors can run again after a break. He ran again in 2015, winning a special election to serve the remainder of David Chiu's term, and was re-elected to full terms in 2016 and 2020.

Peskin is the longest-serving Board of Supervisors member in history.

Sign up for GrowSF's weekly roundup of important SF news!

Policy positions & priorities

An enduring presence in San Francisco politics, Supervisor Peskin was first elected to the Board in 2000 as part of the progressive vanguard seeking to check the centralized power wielded by Mayor Willie Brown. A prolific legislator and long-time power broker, Peskin has spent decades leveraging his political power to reduce the mayor's power and to obstruct the meaningful construction of housing in the city.

Housing

Perhaps no politician in the modern era is more responsible for the city's housing crisis than Aaron Peskin. Almost every root cause of the housing shortage—including empowerment of neighbors to single-handedly block projects; abuse of environmental laws; extensive bureaucracy, taxation, and fees; the alignment of far-left politicians with housing opponents; and frequent interference with specific projects by the Board of Supervisors—has been created, exacerbated, or encouraged by Peskin throughout his many years in office.

Peskin's work to block housing development began early: as a student at UC Santa Cruz, he filed a lawsuit to stop the university from building dorms. As he would often do to attack housing in San Francisco, he used environmental law as the basis for his suit—the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA, is frequently abused by housing opponents. Upon moving to San Francisco he continued his anti-growth mission, becoming president of the Telegraph Hill Dwellers, described by the Chronicle as "a powerful lobbying group that is deeply opposed to development." Under his leadership, the group blocked an expansion by City College in Chinatown. Before joining the Board of Supervisors, he worked to make CEQA complaints directly appealable to the Board. When his first term on the Board began in 2001, he immediately joined its Land Use Committee, where he focused on giving the Board more control of the city's Planning Commission and Board of Appeals (which rule on neighbor objections to housing projects).

By the time term limits forced Peskin off the board, he was established as "an unapologetic foe of development who earned his stripes fighting new projects." Living up to that reputation, he continued warring against housing as a private citizen. He once again used a neighborhood group, this time "Citizens for a Sustainable Treasure Island," which sued to prevent the development of 8,000 homes on the man-made island in the bay.

Peskin's anti-housing crusade continued after he rejoined the Board in 2016. In his second round as a supervisor he has opposed everything from building 495 units of housing on the site of a valet parking lot, to streamlining the city's Kafkaesque permitting rules; to converting a single-family townhome to condominiums. As Board of Supervisors President, Peskin has the power to appoint three of the seven commissioners on the main body that reviews housing disputes, the Planning Commission. He can also use the Historic Preservation Commission, which he created in 2008 (all seats on which require Board of Supervisor approval, of course), and which can shut down changes to any building or place deemed to be of historical interest. A favored tactic has been to threaten properties with landmark status to bring approval under the purview of the commission - even questionable "landmarks" like the interior seating configuration of the Castro Theater.

Notably, Peskin is a landlord who rents out three houses (the most of any member of the Board of Supervisors), and he benefits financially from housing scarcity (which keeps rent high). He also lives in a home formed by merging what was once a rent-controlled duplex. His merged home was discovered shortly after Peskin proposed legislation to ban turning smaller units into larger homes; critics noted the apparent hypocrisy, along with questionable details like Peskin having apparently bullied the former owner into selling the home to Peskin's family at a $700,000 loss. The Department of Building Inspections found that Peskin's use of the entire duplex was not technically illegal: the two units weren't officially merged into one because both halves of the building still had kitchens.

While Peskin has done much to earn his reputation as an arch-NIMBY, he has occasionally been willing to support housing, especially if it's far from his district. He previously supported the Hunters Point Shipyard redevelopment, a development in Parkmerced, and upzoning of certain eastern neighborhoods in the city. And after the state threatened to take away the city's ability to restrict housing unless San Francisco meets minimum building requirements, Peskin was willing to join the mayor in passing pro-housing legislation. As sentiment in the city shifts in a more housing-friendly direction, we may discover that Peskin's interest in winning elections tames his desire to block housing—at least, as long as it isn't in his North Beach neighborhood.

Limiting Mayoral Power

San Francisco once had a "strong mayor" system, in which the mayor was largely responsible—and accountable—for the way the city ran. From the moment he first became a supervisor in 2001, Peskin has worked to shift power away from the mayor's office, distributing it to the Board of Supervisors either by the creation of unelected commissions to oversee a city department or by shifting the power to appoint commissioners away from mayor's office. Sometimes he used both tactics in tandem. In practice, this means that Mayor Brown, elected in 1995, directly controlled 19 departments and the Board of Supervisors controlled 3 departments. In 2023, Mayor London Breed controls 12 departments and the Board of Supervisors controls 16.

Interested in the details? Learn more in GrowSF's detailed report on how Peskin killed San Francisco's strong mayor system.

Crime & Drug Use

Peskin vociferously supported defunding the police in 2020, calling a $120 million reduction in the SFPD budget "a reasonable first step" and declaring himself a "proud supporter" of removing police staffing minimums (now, years later, the city has a severe police shortage). He opposed recalling former DA Chesa Boudin, who voters ousted after Boudin took a lax approach to crimes like public drug abuse and petty theft, even as viral theft incidents became commonplace and overdose deaths skyrocketed.

Since Boudin's recall, Peskin has "seemed to move to the center on drug dealing and use on public streets," although the change may be more style than substance. For example, Peskin demanded that Mayor Breed take questions from the Board of Supervisors in a drug-saturated public plaza instead of within City Hall. He had to stop the meeting after only 11 minutes, when anti-police protestors drowned out Peskin's voice; as the meeting concluded, one protester threw a brick that hit a high school student in the audience. Peskin has demanded that Breed "shut down all public drug dealing in open air sites . . . in the next 90 days," but he expressed no willingness to fund the effort, claiming that the problem was not one of resources, but of coordination.

Environment

Environmentalism is one of Peskin's stated priorities, but his brand of environmentalism seems to primarily focus on preservation at all costs and many of his political moves—especially fighting against housing density—fly in the face of evidence for the greater environmental good. When not in office, Peskin is President of a Nevada environmental non-profit.

Streets and Transit

Supervisor Peskin generally favors public transit and bicycles, but his support is inconsistent and he has repeatedly reversed himself on transit issues.

-

In 2007, he authored (and passed) a comprehensive set of reforms to MUNI governance and funding, stripping influence away from the Board of Supervisors and giving the system more reliable and more flexible funding. He has since called the reforms an "abject failure" and proposed stripping the city transit authority of its ability to raise fares.

-

Peskin initially backed the Central Subway System before reversing course and opposing it.

-

He's a member of the Vision Zero committee, which aims to completely eliminate traffic deaths in San Francisco, but opposes safer alternatives to cars like autonomous vehicles, scooters, and stationless bike sharing programs.

-

He voted for Great Highway to stay closed to cars on weekends, but voted against car-free JFK.

-

He seems generally opposed to parking lots, unless people are trying to turn those parking lots into housing—then he's pro parking lot.

One theme that does seem consistent: as a cyclist himself, Peskin is often in favor of bikes and more traditional forms of transit, but generally opposes transit ideas from tech companies (e.g., ride sharing, scooters, bike-shares, or self-driving cars).

Fun

Peskin has developed a reputation for hindering fun events across the city. In his first term, a landmark San Francisco bar was temporarily shut down after a group of neighbors, including Peskin's wife, complained about it. Once the Peskins got involved, city officials rescinded the bar's authorization to operate without serving food. Next, Peskin managed to shut down the San Francisco Grand Prix, an annual bike race that used to take place in North Beach. Peskin claimed that the event's sponsors owed the city money for traffic cops deployed at the event, saying it was: "a problem, a very serious problem. I am outraged!" Not long after that, the city's Parks and Recreation department denied an alcohol permit to the North Beach Festival for the first time in 30 years; the festival's sponsor attributed the denial to political pressure from Peskin.

Between his supervisor stints, Peskin sued the America's Cup boat race. As he so often has, he used a neighborhood group—this time "Waterfront Watch"—to file an environmental lawsuit. He sought to prohibit the race from preparing team or spectator sites along the waterfront, which would "doom the races" if he succeeded. The race went forward that year, but it left San Francisco for Bermuda afterward; Peskin had "no regrets" about the event's departure.

After returning to the Board, Peskin waged a small war against the Golden Gate Park ferris wheel. Despite approval from two separate city committees to extend the ferris wheel for four years so that SF families and visitors can have fun, Supervisors Peskin and Connie Chan dragged the contract before the full Board of Supervisors for review under the pretense that the ferris wheel, a temporary installation, was in fact a "permanent structure." Peskin tried to overrule the four year extension, but ultimately lost the vote. Peskin then tried to argue that the ferris wheel would require two thirds Board of Supervisors approval, due to the revenue sharing component of the deal. We can only speculate on his intentions. Did it do it because he's against fun? Because, perhaps, he really hates ferris wheels? Or... maybe he just really wanted the ferris wheel to be in his district.

Personal scandals

No one's ever accused Aaron Peskin of being too nice. Although he seems to have tempered his most abrasive tendencies in recent years, Peskin's behavior during his first two terms caused reporters to dub him the "Napoleon of North Beach." He has a documented history of calling to harangue various political leaders late at night, often while drunk, and in particular for targeting female department heads. What is it like to be on the other side of Aaron Peskin late night call? Well, he might threaten your job or move to disband your entire department, just because you dared to disagree with him. Eventually, Peskin's political opponents were so frequently and severely harassed that they began going public and filing misconduct complaints.

-

The Executive Director of the Port of San Francisco filed a complaint and sent a letter to then-Mayor Gavin Newsom's office reporting that Peskin threatened the jobs of port members, harassed her repeatedly, and threatened that he'd be "going after her."

-

Newsom's director of climate protection initiatives went public with allegations that Peskin twice threatened to eliminate his job out of spite. In a strange coincidence, Peskin introduced a measure that would have slashed the city Department of the Environment, but the city attorney deemed the measure illegal.

-

Another city supervisor reported that Peskin retaliated against her by switching his vote and killing one of her initiatives, and told her: "Payback is a bitch." Peskin responded, on record to the Chronicle: "She's a whiny brat, and she has been a whiny brat ever since she arrived at the Board of Supervisors."

With these reports the floodgates opened, and Peskin's abusive behavior became a topic of public discussion. As Gavin Newsom put it: "Everyone's been hearing this for years. I don't think there's a person in city government who's surprised . . . I don't think anyone that I've met in elected office or a community leader hasn't received these types of calls."

When Peskin ran for re-election, he promised that he had changed: "I have learned and listened and grown and matured." Sadly, he had not. In 2018, he showed up at a burning building, intoxicated and out of control, profanely insulted the fire fighters, tried to give them commands, and lambasted the Fire Department chief (who was female) for not answering his calls during the fire. After the chief criticized Peskin for interfering with an active fire scene, he issued an uncharacteristic apology. But his bad behavior continued. In 2021, after continuing reports of abuse, and of showing up to work intoxicated, Peskin announced that he had entered alcohol treatment and attributed his past misconduct to drinking. Even that was not the end, though. In 2022, Peskin had to publicly apologize again for remarks implying that a transgender supervisor candidate wasn't "real" or "human." And in 2023, he was caught on tape calling a community leader from his district "a horse's ass" at a Board of Supervisors meeting.

Key votes and actions

Aaron Peskin has been in power for a long time and has taken countless positions on issues. With that in mind, here are some of the highlights (with an emphasis on his more recent moves):

Education

-

Peskin opposed the overwhelmingly popular 2022 recall of School Board Members Alison Collins, Gabriela López and Faauuga Moliga. He, in fact, endorsed Collins in 2018.

-

The day after the recall election, he wrote Prop C, proposing a charter amendment to limit voters' ability to recall candidates. Prop C was defeated at the ballot.

-

Peskin was the lone vote against helping the SFUSD cover the $3.2 million required for the recall election, roughly the equivalent of 30 teacher salaries. He actually voted against this twice.

Transportation

-

We have Aaron Peskin to thank for the runway shortage at SFO. Peskin, along with Supervisor Tom Ammiano, killed the SFO runway expansion project in 2007.

-

Also in 2007, Peskin authored and passed a proposition to free MUNI governance from political interference. This was an ambitious and commendable act of reform aiming to provide MUNI with more reliable funding.

-

But he no longer supports these changes, which he now considers an "abject failure" since the SFMTA Board of Directors has dared to actually act independent of what he wants them to do.

-

In 2020, Peskin and Supervisor Preston proposed a charter amendment to strip the board of the authority to decide fares, successfully pressuring the board to drop a proposed fare increase.

-

He proposed a charter amendment (with Supervisor Safai) to require the Mayor to approve any fare increases.

-

-

Peskin has supported transit projects in his district. He initially backed the creation of the Central Subway (but later changed his mind) and supported the redesign of Jefferson Street in 2013 to be more bike and pedestrian friendly.

-

In 2019, Peskin took a run against every form of new vehicle sharing in SF. He lobbied against the expansion of electric scooter sharing; killed an attempt to introduce dockless bike sharing to SF, calling it an "example of tech arrogance"; and levied an additional tax on ride sharing companies.

-

Peskin voted to keep Great Highway closed to cars on weekends, but he voted against a car-free JFK

-

Most recently, Peskin opposed the CPUC decision to allow driverless taxi companies to expand their service and charge for fares.

Crime

Like many progressive leaders in San Francisco, Peskin has actively worked to defund and impede the SFPD, while at the same time blaming the police department and the mayor's office for not doing enough to combat crime.

-

Did you know that the SFPD has to get approval from the Board of Supervisors to use surveillance technology? Peskin sponsored and passed a 2019 ordinance prohibiting police use of any new surveillance without explicit board approval. While provisions prohibiting facial recognition received the headlines, the restrictions were far broader.

-

Peskin supported defunding the police, calling a $120 million reduction in the SFPD budget "a reasonable first step" and declaring himself a "proud supporter" of removing police staffing minimums.

-

Opposed recalling former district attorney Chesa Boudin.

-

Pushed through the early re-appointment of progressive commissioner, Cindy Elias, before other candidates could apply and be considered.

-

In 2023, Peskin proposed a last minute amendment to city budget to eliminate positions within the SFPD command staff, single-handedly impeding a multi-month budget approval process so he could...yell at Police Chief Scott about property crime levels? He eventually succeeded in passing legislation to eliminate one assistant chief and one commander at the police department, a move that Peskin claims will somehow retain district captains by slowing the pace of promotion.

Governance

-

Has systematically reduced the power of the office of the Mayor through the creation of commissions to oversee city departments and shifting control of these commissions to the Board of Supervisors.

-

Supported an effort to interfere with legally required redistricting, in an attempt to gerrymander districts for progressive supervisors.

-

Killed a "no brainer" proposal to limit the ability for individual citizens to impede city projects done for public safety or health, including frivolous CEQA objections.

-

Led the Board of Supervisors initiative to ensure the retention of John Arntz, the widely respected city Elections Chief, after the Elections Commission voted to launch a search for new candidates in the name of racial equity.

-

Proposed and passed legislation eliminating remote public comment at Board of Supervisors meetings.

Housing & Development

-

Created the Historic Preservation Commission, giving it broad powers to supersede decisions made by the Planning Commission. The HPC has deemed not only buildings but entire neighborhoods, like St. Francis Wood, historic, making them "exempt from SB9, SB10, and SB35" (California state bills that boost housing density).

-

In 2010, Killed a condo tower at 555 Washington Street, by rejecting the (pre-approved) environmental report. According to the project architect, "the only thing Aaron Peskin wanted was no project."

-

Sued the city to halt development on Treasure Island, gumming up a project approved in 2011 that would have brought 8000 new homes (25% of which was affordable housing stock). The suit was finally denied by the State Supreme Court in September of 2018.

-

Tried to create yet another housing commission that would have given the Board of Supervisors control over two additional mayoral departments. The measure failed to pass at the ballot.

-

Proposed the Protect and Preserve Act, which would have dramatically slowed approval of basic home upgrades, in the name of penalizing large home construction. This bill was roundly criticized and even Peskin eventually admitted it was too broad in scope.

-

Voted to delay upzoning a transit-rich area in district 6 to conduct a "race and equity study" that never happened.

-

Opposed the development of 495 units of family-sized housing, which would have been built on a Nordstrom valet parking lot.

-

Peskin, alongside Supervisor Chan, played a key role in obstructing Mayor London Breed's 2022 attempt to streamline the city's byzantine housing development process.

-

Peskin and Chan first refused to advance Mayor Breed's charter amendment out of committee and then, when the issue finally reached the ballot (as Prop D), introduced a competing amendment, Prop E, which they misleadingly titled "the Affordable Housing Production Act."

-

The SF Chronicle described the ballot initiative as "cheap political theater," noting that the bill manages to be "both redundant and a step backward."

-

SPUR called the bill "a measure that was designed to block the passage of Prop D," concluding that the new measure "would do nothing to significantly improve the approvals process for housing projects in San Francisco."

-

The move succeeded in blocking Prop D, with both propositions failing at the ballot box.

-

-

Voted against redevelopment of 1151 Washington Street, a project that would replace a single family home with 10 townhomes, over concerns that the building would cast shade over a nearby recreation center.

-

Tried to landmark the interior seating configuration of the Castro Theater, which would have blocked plans to update and save the failing venue, but lost the final vote.

-

Opposed Mayor Breed's second attempt to streamline planning code and the use of discretionary review (the Constraints Reduction Ordinance), leaving in place a process that can drag out new construction and renovation for years.

-

Faced with the need to revitalize downtown, the fact that housing development in the city has slowed to a crawl and the looming state mandate that could strip the city of the ability to restrict development projects, Peskin joined Mayor Breed in jointly passing a series of new legislation aimed at jumpstarting development by:

-

easing the conversion of downtown office buildings to housing;

-

allowing developers to satisfy the affordable housing requirement by paying for affordable housing off-site;

-

temporarily reducing the proportion of affordable housing required for new and already approved development projects and deferring developer impact fees; and

-

putting a $300 million housing bond on the March 2024 ballot to pay for affordable homes.

-