San Francisco’s approach to homelessness is called “housing first.” This sounds great, but it only serves about one third to one half of homeless people well. Many people need psychiatric care, many others need drug and alcohol treatment, and some need full-time supervision. Our system fails these people, and rather than end up indoors they bounce between a tent and the emergency room. Here’s how we got here.

In 2002, a legislative analyst report requested by Gavin Newsom, who was then the District 2 Supervisor, found that San Francisco’s Cash Assistance programs were the highest maximum cash grants in the state (both overall, and per-capita) – and that rather than giving out cash, other Bay Area counties had chosen to provide in-kind services like shelter, clothing, and food. The analysis found that just about every other county switched from providing cash assistance to in-kind services in order to save costs, and that this policy change occurred between 1990 and 1996. The report does not mince words. “We should adopt in-kind services over cash assistance,” it concluded on May 9, 2002.

This 2002 legislative report was the driving force behind Proposition N “Care Not Cash”, sponsored by Gavin Newsom in 2002, and passed by voters the same year. Care Not Cash changed San Francisco’s General Assistance from $395 per month to just $59 per month but came with a guarantee of housing and food for the homeless. The measure stated that if the services weren’t available, the city could not reduce a homeless person’s aid. The idea being: the city’s savings from no longer spending on welfare checks (an estimated $13M in savings at the time) would create more affordable housing, expand shelters, and add treatment beds.

Gavin Newsom’s Care Not Cash legislation marked the beginning of a sea change in San Francisco’s approach to homelessness. It was the first domino to fall that culminated in a 10 year homelessness strategy titled the “Plan to Abolish Chronic Homelessness” – the cornerstone of this plan was above all to provide housing for the homeless, which became known as Housing First.

The New 2004 Plan: “Housing First”

San Francisco’s homelessness policy from the mid 1980s until 2004 was the “Continuum of Care” model, which was made up of three main efforts:

- Prevention through eviction defense, emergency grants, and education.

- Outreach to all people facing homelessness.

- Supportive services including substance abuse treatment, job, training, housing placement, and child care (among many such services).

It was basically a smorgasbord of many different services, outreach programs, and city department efforts.

The 2004 Plan To Abolish Chronic Homelessness set a 10-year plan to end the Continuum of Care approach and move to a Housing First model, committing the majority of our budget and resources to building permanent supportive housing.

As the report describes in its own words, permanent supportive housing was supposed to be more effective, affordable, and humane approach to addressing homelessness:

“The model of housing with on-site supportive services has proven to be most effective in housing persons who have been homeless and struggling with mental illness, substance abuse, and other issues. It is clearly more humane and cost effective to provide someone a decent supportive housing unit rather than to allow them to remain on the street, and/or ricochet through a high cost setting such as the jail system or hospital emergency rooms. Such institutions offer incarceration or treatment, but are no more than expensive revolving doors leading back to the streets.”

- The San Francisco Plan to Abolish Chronic Homelessness, Page 25

Measuring outcomes

It has now been over two decades since San Francisco adopted the Housing First model. And the first lines of the 2004 strategy still sound eerily similar to the headlines of today: “San Francisco is Everyone's Favorite City. But San Francisco also has the dubious distinction of being the homeless capital of the United States.”

To consider the outcomes of the Housing First model, we draw our evidence from one of SF’s most comprehensive policy reports which tracked 1,818 people who were homeless over eight years, from 2007 until 2015. Specifically, the report tracked adults as they entered and moved through San Francisco’s Housing First programs.

Note: Data on the effectiveness of San Francisco’s Housing First efforts gets more complicated to decipher after mid-2016 when the Department of Housing and Homelessness was created, due to a complete reorganization of funding, outcomes tracking, and policy research. We hope to follow up this report with more analysis of the recent data.

Our city’s Housing First model has had three major implications:

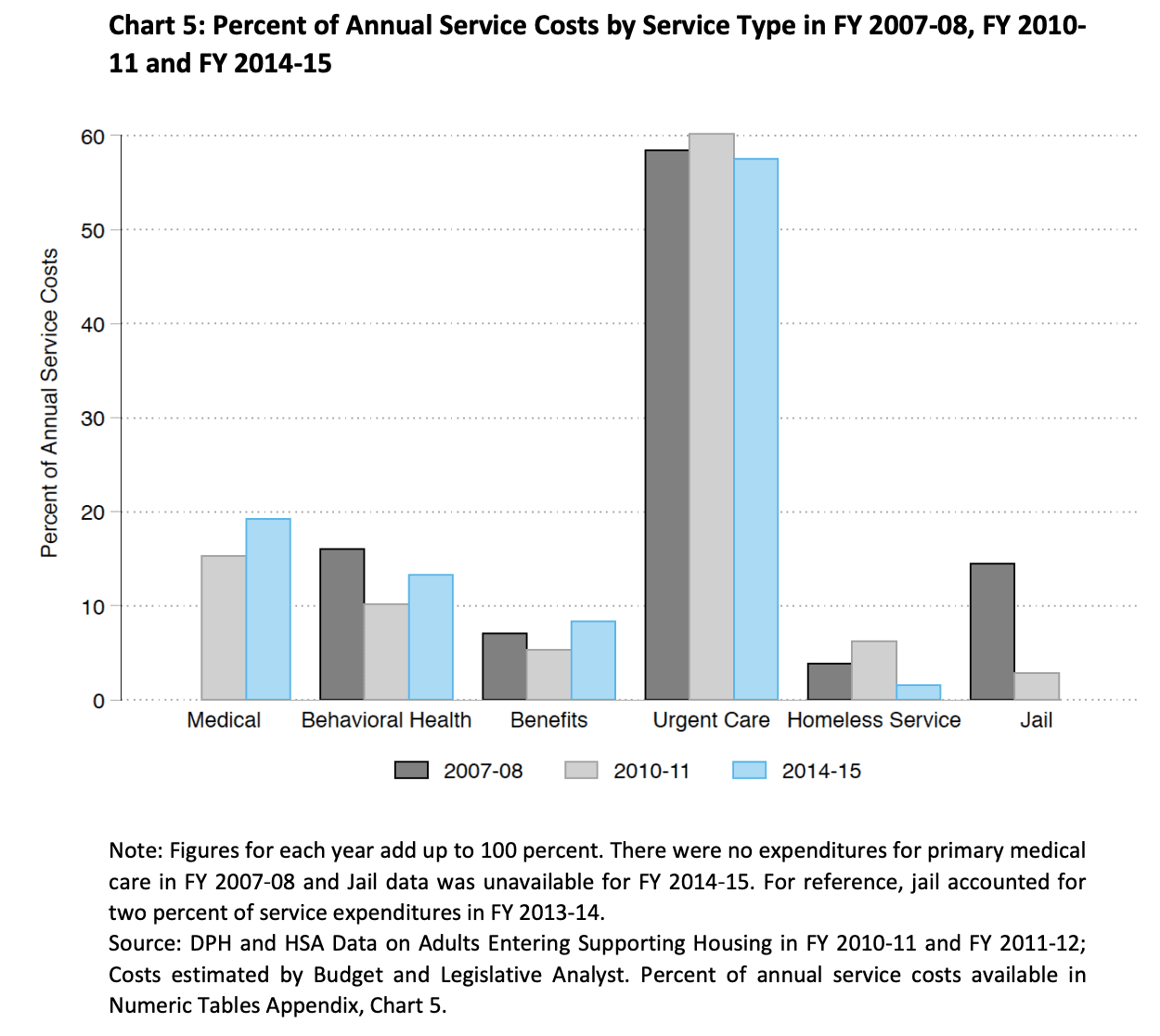

1. The Vast Majority of Homelessness Costs come from Emergency Room / Urgent Care: 57% of all costs from 2007-2015

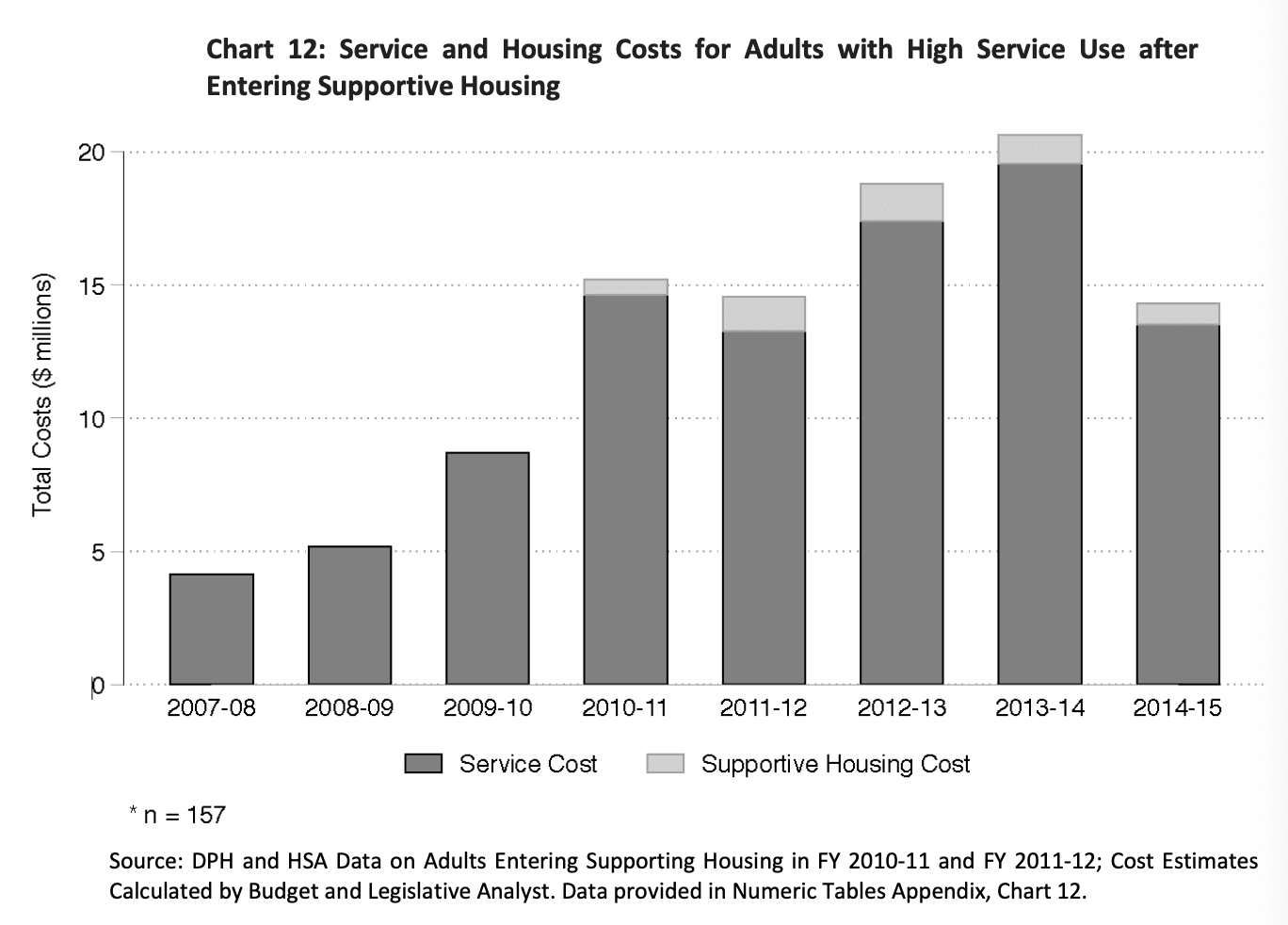

Between 2007 and 2015, the majority of money spent on homelessness in San Francisco went towards emergency and urgent care, including emergency department visits, psychiatric emergencies visits, and ambulance transports. Across all 1,818 people that the policy report tracked, emergency/urgent care costs accounted for 57% of total costs. The actual cost of the supportive housing was negligible compared to the service costs that included emergency care.

While there has not been a report as comprehensive as this one since 2015, documentation of the ongoing cost burden of emergency care continues. For instance, a 2019 Fire Commission meeting noted that over 40% of San Francisco’s homeless population use the city’s ambulance service. And moreover, that there were outstanding costs of at least $50M that the Department of Homelessness should pay.

A 2023 hearing from the SFFD confirmed that this trend has continued, noting that 25% of all ambulance trips involve people who are homeless. And over a five-year period, 5 chronically homeless individuals took over 1,800 ambulance trips, costing the city $4M in transportation costs alone. The sad reality is that despite the amount of trips they took to the hospital, their outcomes were not notably better: two of them died, two remain in shelter, and one remains in mental health conservatorship.

2. The Greatest Costs come from an Extremely High-Need Minority: 16 people cost SF almost $1M each

Before going into supportive housing, just 162 adults, 9% of the total homeless population, cost $113.6M over 8 years, accounting for 42% of total service spending. 81% of that ($92.3M) was spent on emergency/urgent care costs. In their most expensive years, each of these adults cost the city $182,428 due to emergency room visits.

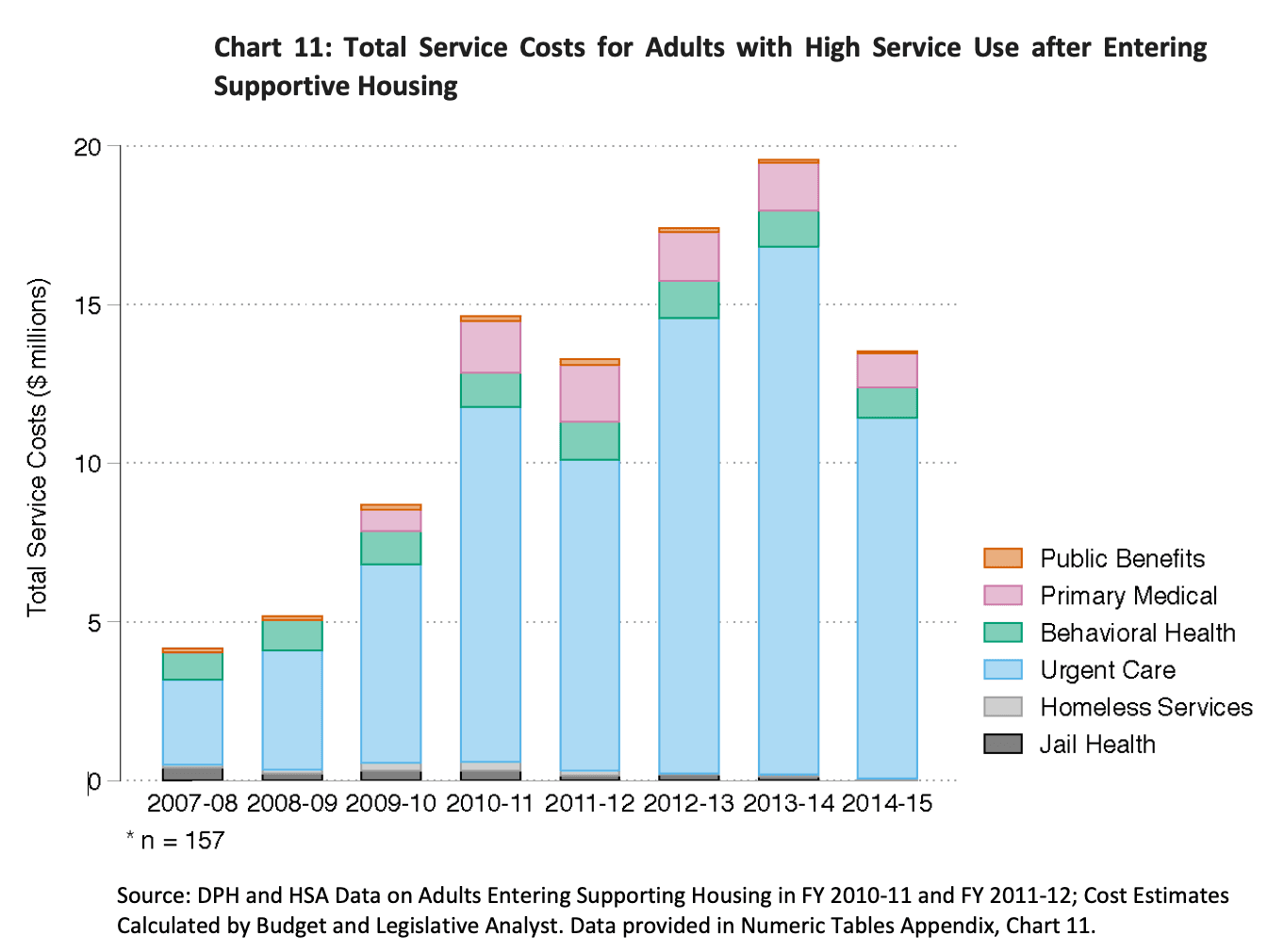

After entering supportive housing, however, the outcomes were just as bad. 157 adults made up for the top 10% of service users by cost, and 79% of all spending on this group was on emergency/urgent care. And importantly, spending on services increased 352% during their time in supportive housing – the vast majority of which was spent on urgent/emergency care. However, some of that increase is due to general cost inflation which affected all groups, according to the report.

Across the high service users, 58 people were consistent across both groups (before entering supportive housing and after). These 58 adults cost $54.4M in services. Of these 58 adults, 16 of them died after placement in supportive housing. These 16 adults comprised 28% of the overall spending on services for the group of 58 adults, making up $15.1M of the $54.4M spent.

That’s almost $1M per person.

3. Our Emphasis on Housing First has Distracted us from More Humane and Cost-Effective Solutions For Those Who Need the Most Help

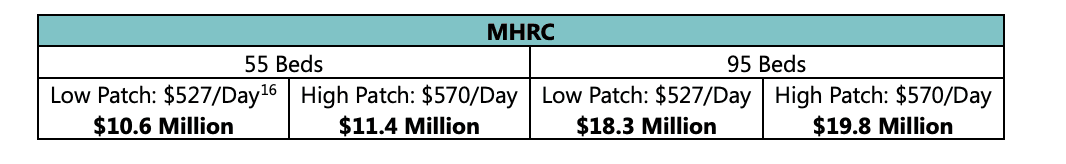

Placing the highest need people into a Mental Health Rehabilitation Center (MHRC), which offers 24/7 intensive psychiatric care, nursing care, and psychosocial rehabilitation services to adults with severe mental illness and/or placed under conservatorship is more humane and cost-effective than letting people languish in supportive housing with emergency room visits.

24/7 care would result in fewer ER visits, better health, better quality of life, and less trauma on the street. And it would save taxpayers 20% - $41M instead of $54M.

The average length of stay at a Mental Health Rehabilitation Center in San Francisco is 2.2 years. So at $527 per day, that’s $24.5M for 58 people. After that, these people can go to a lower-intervention center, but still be cared for. If they were to move to an Adult Residential Facility which provides basic care and supervision, that would cost $200 a day. For 58 people, that’s $16.9M for 4 years. Meaning 6 years would cost a total of $41.4M and likely result in fewer deaths and more humane outcomes. That’s $10M less than the revolving door of supportive housing and emergency room visits, but importantly, it would likely be a more humane path for those who need the greatest help.

| Current Housing-First Model ($54.4M) | Treatment-First Model ($41.4M) |

|---|---|

| Fast-tracked into Supportive Housing | Placed in a Mental Health Rehabilitation Center for 2 years ($24.5M) |

| Remains in Supportive Housing with constant emergency room visits | Placed in an Adult Residential Facility for 4 years ($16.9M) |

For the people who need more dedicated medical care, Housing First seems callous: it is a way of concealing the problem by shepherding those who cannot take care of themselves into private rooms out of the public eye.

Housing First is not the right solution for untreated mental illness or drug addiction. Placing those who need medical attention in supportive housing is nothing more than hiding the problem. Those who need medical care, as the evidence shows, will continue to revolve in and out of emergency rooms rather than getting the sustained care that they need.

To implement this better approach, though, we must first expand the facilities that provide these services. San Francisco has a shortage of mental health treatment beds, but building more will save us money and keep more people alive.

Generate a Personalized Email to the Board of Supervisors

To:

Sign up for the GrowSF Report

Our weekly roundup of news & Insights