San Francisco has the longest city charter in America

April 21, 2025

The city charter is the constitution of San Francisco. It’s time to rebalance and modernize it.

To understand San Francisco, you need to understand our city charter. And to fix the problems in San Francisco, you need to fix our charter.

Think of our charter, basically, like our city’s constitution: it determines what the city can and cannot do, and what you can and cannot do. The original SF charter was created in 1898, and over time charter amendments made it too complex and hindered the operation of an effective government (there were over 500 charter amendments passed between 1932 and 1978). This kicked off an initiative to write a new, simpler city charter which voters approved in 1996. The 1996 charter was 173 pages when it was first approved by voters. In the last three decades, we’ve added 365 pages. That’s about 12 pages per year. Our charter is now over 538 pages total.

San Francisco’s government is run by this 538-page Charter. Buried in those pages are rules like the 61 procedural steps across 11 city departments to open a small business, five overlapping commissions to address homelessness, and a policy that prevents the mayor from directly hiring the police chief. Every one of those rules comes from the Charter.

So in this spirit, today we’re starting a series on San Francisco’s charter and why it's time to rebalance and modernize it. We'll take a look at some of the rules we have on the books to give you an idea of how important the charter is, and why it is so urgent that we fix it.

But first:

1. At 538 pages, San Francisco has the longest charter in America

San José’s charter is 81 pages, San Diego’s 149, and Sacramento’s is just 50.

San Francisco has added amendment on amendment into its City Charter, turning it into the longest local constitution in America. Many of the city’s biggest challenges—like unaffordable housing, unsafe streets, and struggling public schools—can be traced back to the complex and cumbersome processes baked into our charter.

| City | Charter Length | Population | Consolidated City-County |

|---|---|---|---|

| San Francisco | ~538 pages | 808,988 | Yes |

| Los Angeles | ~352 pages | 3,820,914 | No |

| New York City | ~340-400 pages | 8,260,000 | Yes |

| Philadelphia | ~170 pages | 1,550,542 | Yes |

| Houston | ~100 pages | 2,314,157 | No |

| Chicago | No charter | 2,664,452 | No |

2. Some commissions oversee nothing, others just duplicate work

San Francisco’s charter has a commission that oversees a department that does not exist. The Department of Sanitation and Streets and its oversight body, the Sanitation and Streets Commission, were created in November 2020 when voters approved Aaron Peskin's Prop B. It also created the Public Works Commission to oversee the Department of Public Works.

Then in 2022, voters passed another measure (also aptly titled Proposition B, and also written by Aaron Peskin) that reversed the 2020 decision. The measure eliminated the newly formed Department of Sanitation and Streets, transferring the responsibility back to the Department of Public Works. However, the measure did not eliminate the Sanitation and Streets Commission, leaving the commission to oversee a department that literally no longer exists.

This is a small, somewhat silly, example of the charter's dysfunction. But it speaks to deep dysfunction that needs to be addressed.

The reality of our city commissions is a spectrum: some commissions have become unaccountable and duplicative, while others provide important civilian oversight to otherwise opaque public problems.

Here are two examples:

The Building Inspection Commission, rather than serving as independent civilian oversight bodies, served the needs of its president, Rodrigo Santos, who in 2020 pleaded guilty to defrauding clients of $775,000, paying out a building inspector, and using the commission to his own personal advantage. The commission has been the subject of multiple controversies.

A 2024 report by the San Francisco Civil Grand Jury titled “Commission Impossible” recommended that 15 commissions be shut down due to redundancy or simple lack of effectiveness.

Table 1: Commissions Recommended for Abolishment Due to Unproductivity

| Commission Name | Reason for Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Advisory Committee of Street Artists and Craftsmen Examiners | Redundant; recommend Arts Commission perform this activity. |

| Advisory Council to the Disability and Aging Services Commission | Redundant; recommend merging into Disability and Aging Services Commission. |

| City Hall Preservation Advisory Commission | Redundant; recommend merging with Historic Preservation Commission. |

| Early Childhood Community Oversight and Advisory Committee | Redundant; recommend merging into Children and Families Commission. |

| Food Security Task Force | Redundant; recommend Human Services Agency perform this activity. |

| Free City College Oversight Committee | Redundant; recommend City College Board of Trustees perform this activity. |

| Housing Stability Fund Oversight Board | Redundant; recommend Mayor's Office of Housing and Community Development perform this activity. |

| Long Term Care Coordinating Council | Redundant; recommend Department of Disability and Aging Services perform this activity. |

| Mayor's Disability Council | Redundant; recommend merging into Disability and Aging Services Commission. |

| Public Utilities Revenue Bond Oversight Committee | Redundant; recommend City Service Auditor perform this activity. |

| Rate Fairness Board | Redundant; recommend Public Utilities Commission perform this activity. |

| Sanitation and Streets Commission | Obsolete; Sanitation and Streets Department no longer exists. |

| Service Provider Working Group | Redundant; recommend spinning off as an entity unconnected to the city. |

| Shelter Grievance Advisory Committee | Redundant; recommend Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing perform this activity. |

| Sweatfree Procurement Advisory Group | Redundant; recommend Office of Labor Standards perform this activity. |

3. Our city bans businesses with more than 11 locations in the world – here’s how the Charter keeps that rule in place

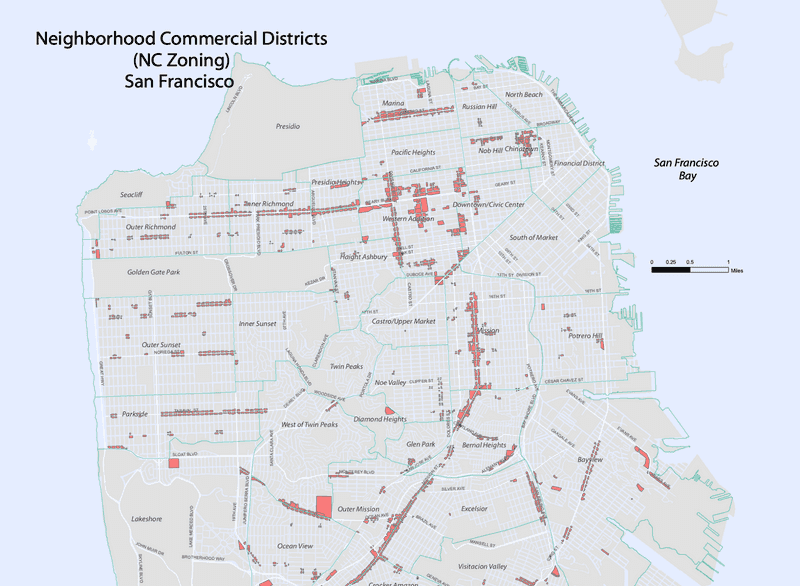

In San Francisco, “formula retail” refers to any business with 11 or more locations worldwide that shares standardized features like signage, branding, and decor. These businesses can't just open shop freely. Since 2004, city ordinances have required them to get special permission from the Planning Commission and, often, the Board of Supervisors.

By 2006, voters passed Proposition G sponsored by Aaron Peskin, expanding these restrictions to nearly all neighborhood commercial districts. While this expansion wasn’t part of the Charter itself, it was approved directly by the voter making it permanent until future voters either repeal or change it. The Board of Supervisors, Mayor, or Department heads can’t undo it on their own.

So while the restriction on formula retail isn’t embedded in the Charter, the Charter sets up a structure where voter-adopted laws become virtually permanent unless there's another ballot measure to change them. In effect, the Charter acts like glue: it makes policy changes extremely difficult to reverse unless the entire city agrees.

This is why, when a business like Trader Joe’s tries to open in San Francisco, they’re stuck in red tape for years. The Hayes Valley Trader Joe’s famously took nearly a decade to get approved.

At the same time, the Board of Supervisors recently passed a new ordinance requiring six months' written notice before a supermarket can close — and it mandates meetings with city departments to “try to stay open.” This isn't in the Charter either, but it’s the same pattern: well-meaning but rigid regulations that make both opening and closing a store unnecessarily difficult.

So while the Charter doesn’t directly prohibit a new Safeway from opening, it does help entrench a system where rules that make it hard to open and close stores become almost impossible to change — even when they're not working. That’s the kind of structural dysfunction that leaves San Franciscans wondering why change never seems to come.

It’s Time to Rebalance and Modernize Our Charter

As a city, we are no strangers to changing our charter. Since the City Charter was passed in 1996, San Franciscans have considered over 111 charter amendments across 27 different ballots. Of these, 81 were approved and 30 were rejected – a 72% success rate of amending our charter.

It is time to rebalance and modernize our charter. Our city is being held back by a charter made for a time that no longer exists.

Generate a Personalized Email to the Board of Supervisors

To:

Sign up for the GrowSF Report

Our weekly roundup of news & Insights