1. San Francisco’s streets are engineered for speed, not safety

Walking in San Francisco often feels like a game of chance. Whether it’s a driver speeding through a crosswalk or a near-miss with a car turning too quickly, close calls are a daily reality. Drivers aren’t spared either—they frequently encounter pedestrians darting into intersections, jaywalkers appearing unexpectedly, or runners with earbuds, oblivious to traffic.

These incidents aren’t just anecdotal. They’re systemic in our city. San Francisco’s streets, particularly its extensive network of one-way roads, are designed to move vehicles quickly, not to protect human life. That flawed design has led to tragic results. In 2014, the city adopted Vision Zero, a policy commitment to eliminate traffic fatalities and severe injuries by 2024. But the goal has not only been missed—it’s been tragically reversed. The year 2024 ended up being one of the most dangerous on record, with 41 people killed in traffic collisions, including 24 pedestrians.

2. One-way streets were built for a different city

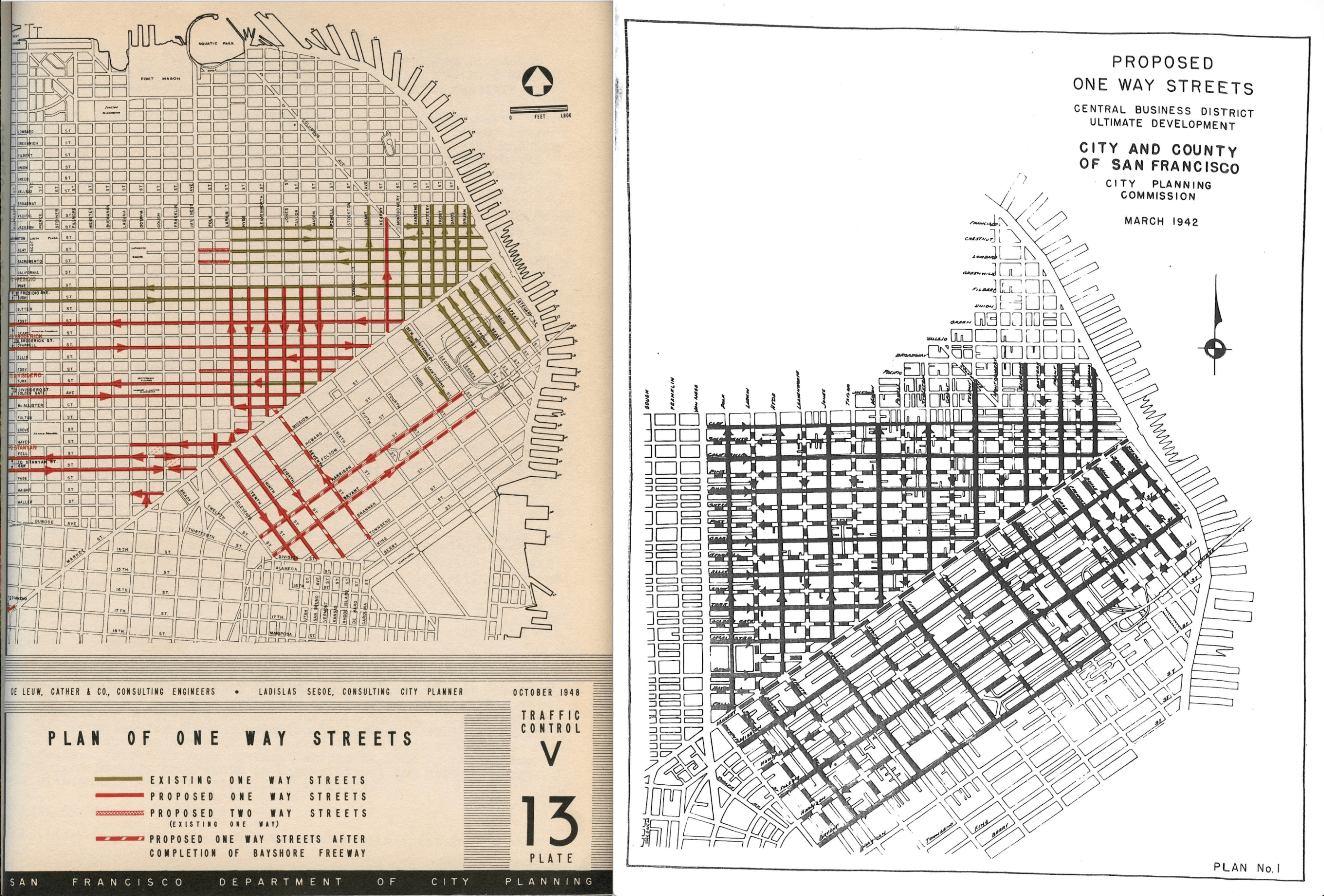

San Francisco’s one-way street system wasn’t an accident, it was a deliberate post-war effort to prioritize vehicle access to downtown. Historian John Freeman notes that the first major one-way conversions, Bush and Pine Streets, were implemented in July 1942. The driving force was the construction of the Union Square Garage, a multi-level parking structure with a 1,700 car capacity meant to boost downtown retail. To make it work, city planners needed to create high-capacity corridors that could deliver drivers from the western neighborhoods directly into the commercial core. This required moving the Dewey Monument, altering pedestrian spaces, and reorienting the flow of traffic around Union Square.

These traffic design changes actually first went to the ballot box. Notably, voters rejected the one-way streets change, twice, in 1922 and 1931. But with war-era emergency powers and a brief window of urban transformation, city leaders pushed the plan forward. The irony is sharp: the first one-way street corridors were launched during World War II, a time when gasoline was rationed, driving was discouraged, and cars sat idle on blocks. One-way streets were being built for a kind of future mobility that didn’t yet exist.

The city eventually expanded the one-way system through several main corridors:

- Bush and Pine, Turk and Eddy, and Clay and Sacramento were designed to funnel drivers downtown from Van Ness.

- Gough and Franklin were specifically aligned to channel vehicles from the Golden Gate Bridge.

This car-centric design philosophy took hold after the war, as public transit use declined and automobile ownership surged. Downtown San Francisco became the region’s retail epicenter, but by the late 1960s, that model began to collapse with the rise of suburban malls, freeway expansion, and population shifts to the suburbs.

As Freeman puts it, “We did this for a lot of outmoded reasons.” These one-way corridors were built to support a mid-century vision of urban life centered on downtown shopping and driving convenience—conditions that no longer define San Francisco.

Source: DeLeuw and Cather's Report to the City Planning Commission on a Transportation Plan for San Francisco (October 1948)

3. One-way streets are built for speed, not safety

The problem is not just that one-way streets are outdated, it’s that they’re actually dangerous. Many of San Francisco’s most injury-prone intersections are either high-speed one-way corridors or wide, multilane streets where fast turns and high volumes of cars clash with dense pedestrian activity. Let’s call these San Francisco’s “mini-highways.”

One-way streets account for 3.8X the number of injuries in San Francisco versus all other types of streets (according to traffic data from 2020-2025).

Left turns off one-way streets are particularly hazardous. Unlike right turns, which are tighter and slower, left turns can be executed at wider angles and higher speeds. A New York City Department of Transportation study found that left turns occur at an average speed of 9.3 MPH, compared to 5.6 MPH for right turns. These faster, smoother turns also create larger blind spots, especially where a vehicle’s A-pillar—the vertical frame between the windshield and side window—obscures the driver’s line of sight. That visual obstruction makes it easier for drivers to miss pedestrians in the crosswalk.

The A-pillar of your vehicle limits your visibility during a left turn

The A-pillar of your vehicle limits your visibility during a left turn

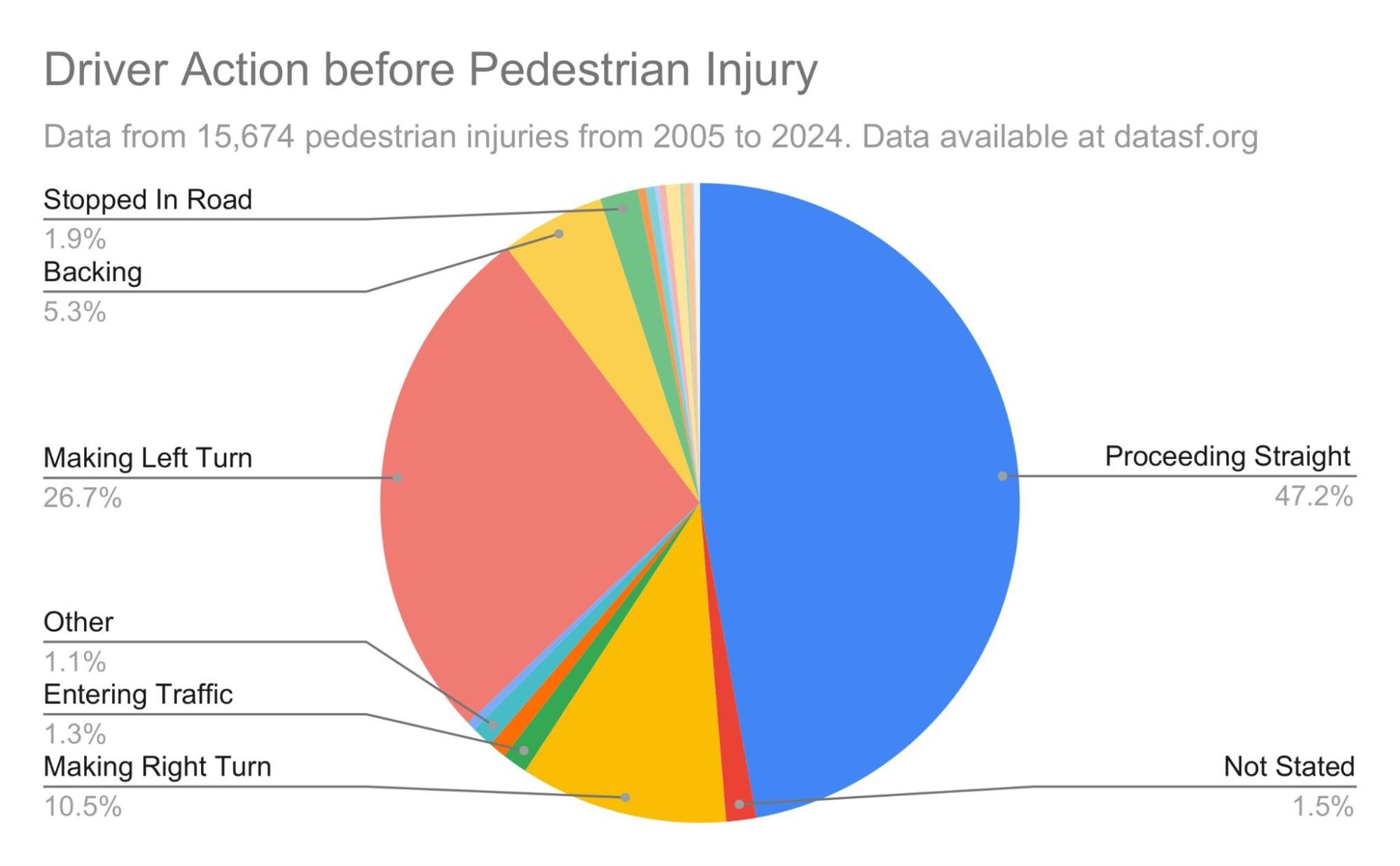

The structure of one-way street grids also leads to more frequent turns. Research shows that these systems generate 120% to 160% more turning movements than equivalent two-way grids. This increases the number of interactions between cars and pedestrians—especially at intersections where left turns are common. This is reflected in the data, with almost 27% of vehicle-pedestrian incidents being caused when drivers turned left given that left turns are both faster, and happen more often in our current system.

These dangers are amplified by the street environment itself. Wide lanes, long blocks, and timed lights create conditions that reward speeding. Drivers often accelerate to catch the next green, treating entire corridors like timed racetracks. Streets like Geary, Van Ness, and 13th Street may not all be one-way, but they function as mini-highways, designed for throughput rather than safety.

It’s no surprise that the city’s most dangerous intersections—such as Gough and Market, 13th and Duboce, and Octavia and Market—are all high-speed corridors where car volume from our mini-highways meets pedestrian density. These designs are fundamentally incompatible with Vision Zero’s safety goals.

San Francisco’s Most Dangerous Intersections For Everyone (2017-2022)

Source: SFMTA Traffic Crashes Report 2017-2022

| Intersection | Injury Crashes (2017-2022) | Total Injured (2017-2022) | One Way Street OR High Speed Two Lane Street | Google Street View |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gough Street and Market Street | 48 | 70 | YES | Market St & Gough St |

| 13th Street, Duboce Avenue, Mission and Otis streets | 43 | 56 | YES | Duboce Ave & 13th St |

| Market Street and Octavia Street | 43 | 58 | YES | Market St & Octavia St |

| Hayes Street and Van Ness Ave | 35 | 58 | YES | Van Ness Ave & Hayes St |

| 8th Street and Mission Street | 35 | 37 | YES | Mission St & San Francisco Bicycle Rte 23 |

| 5th Street and Market Street | 34 | 37 | NO | Market St & Cyril Magnin St |

San Francisco’s Most Dangerous Intersections for Pedestrians (2017-2022)

Source: SFMTA Traffic Crashes Report 2017-2022

| Intersection | Total Injured (2017-2022) | One Way Street OR High Speed Two Lane Street | Google Street View |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyde and Turk Streets | 21 | YES | Turk St & Hyde St |

| 5th and Market Streets | 19 | YES | Market St & Cyril Magnin St |

| Leavenworth and Turk Streets | 16 | YES | Turk St & Leavenworth St |

| Eddy and Taylor Streets | 17 | YES | Taylor St & Eddy St |

| Geneva Ave and Mission Street | 15 | YES | Mission St & Geneva Ave |

| Golden Gate Ave and Hyde Street | 15 | YES | Golden Gate Ave & Hyde St |

| 6th and Mission Street | 14 | NO | Mission St & 6th St |

| Pine and Polk Streets | 14 | YES | San Francisco Bicycle Rte 25 & Pine St |

| San Bruno Ave and Silver Ave | 14 | YES | Silver Ave & San Bruno Ave |

4. Fixing our one-way streets needs a system-wide change, not a reactive approach of fixing one intersection at a time

Street design, not just behavior, is the primary driver of traffic injuries and deaths. If San Francisco is serious about reducing harm, it must start by confronting the legacy of its one-way streets and their role in promoting unsafe speeds and excessive turning movements.

Lowering vehicle speeds is one of the simplest and most effective ways to save lives. According to Vision Zero data, a pedestrian hit at 20 MPH has a 90% chance of survival, but at 40 MPH that drops to just 40%. Between 2017 and 2022, crashes due to unsafe speeds rose by 25%, confirming that current design strategies are failing.

Research on the dangers of one-way streets has been known for a long time. A study published in May 2000 by the Ontario Transportation Department concluded about one-way streets: “The injury rate was 2.5 times higher on one-way streets than on two-way streets and 3 times higher for children from the poorest neighbourhoods than for those from wealthier neighbourhoods.”

There are proven solutions. In Louisville, Kentucky, converting one-way streets to two-way traffic led to a 23% to 60% reduction in crashes and a 15% to 30% drop in crime. In San Francisco, a redesign of Fell Street—reducing lanes and adding a protected bike lane—resulted in a 38% drop in total collisions and a 50% reduction in pedestrian injuries.

Infrastructure matters. Elevated crosswalks, protected intersections, and pedestrian-priority zones significantly reduce conflict. These are not speculative solutions—they’re already working locally.

Ultimately, San Francisco must reckon with the fact that its one-way street network was built for a mid-century retail economy that no longer exists. The city is no longer defined by suburban shoppers driving downtown. It’s time to build a new system—one that puts people, not speed, at the center of its design.

Generate a Personalized Email to the Board of Supervisors

To:

Sign up for the GrowSF Report

Our weekly roundup of news & Insights