The Formula Retail Ban Hurts San Francisco

June 16, 2025

The formula retail ban, which limits chain stores in San Francisco, has led to higher prices, vacant storefronts, and hurt local businesses. Here’s how it came to be and how we can fix it.

San Francisco has strict limits on any business with 11 or more locations in the world. This means that practically every supermarket, hardware store, and coffee shop needs to go through a lengthy, expensive process to obtain a “Conditional Use Authorization” permit in order to open. It has hurt local favorites like El Farolito, Ike's, and Blue Bottle, while failing to keep big chains from out-competing local shops.

The "chain store ban" was originally pitched as a way to protect small businesses, but evidence from the past decade shows it's helped perpetuate vacant storefronts and raised prices for both businesses and consumers. In some cases, businesses have spent up to $100,000 and taken a year to get their permit.

Here's how the "chain store ban" hurts San Francisco, how it came to be, and how we can fix it.

What Is Formula Retail?

Formula retail is, basically, any household brand. Starbucks, Blue Bottle, Trader Joe's, Safeway, Whole Foods, H&M, Nordstrom, Lululemon, Vuori, CVS, Walgreens – you get the idea. You may not know it, but all of these popular stores have been de-facto illegal to open in most of San Francisco since 2006. In order to get their permits, they all spent tens of thousands of dollars on lawyers and appeared in front of an unelected body–the Planning Commission–to beg for special approval for the privilege of selling their goods to San Franciscans (with the latest example happening just last week!).

49 percent of San Francisco’s coffee shops are formula retail, compared to 11 percent of all restaurants. The vast majority of pharmacies over 3,000 square feet and supermarkets over 10,000 square feet are formula retailers, while smaller establishments are much more likely to be independent retailers. More than 80 percent of all banks are formula retail.

- San Francisco Formula Retail Economic Analysis report, p. 4

San Francisco’s formula retail law regulates chain stores in order to control what types of businesses are allowed to operate in the city. Under Planning Code §303.1, any retail business with 11 or more locations worldwide and a standardized appearance (name, décor, signage, merchandise, etc.) is considered “formula retail,” i.e. a chain store.

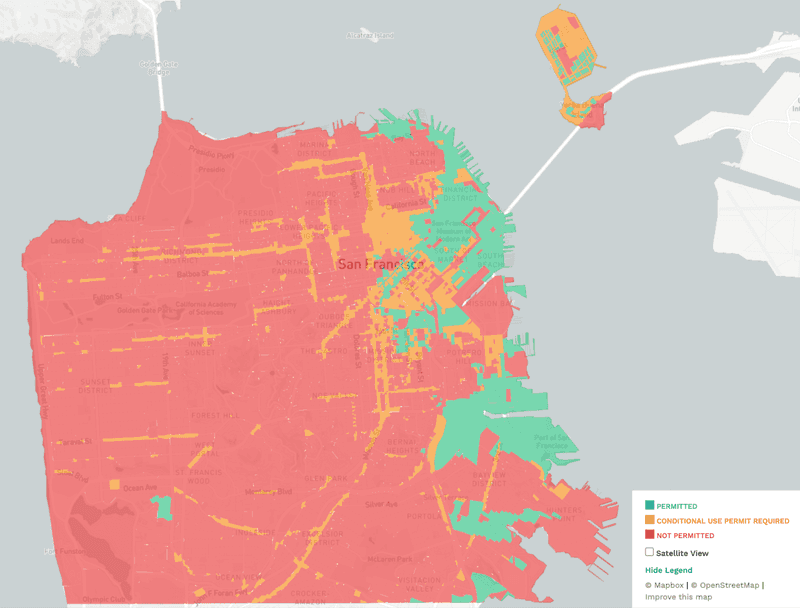

Across San Francisco, formula retail may be banned because the zoning doesn't allow any commercial activity (see the red areas below), or it may be technically allowed but requires a Conditional Use Authorization (the yellow zones below). Some parts of SF do allow formula retail without any extra fights, though (the green areas).

Where formula retail is illegal, somewhat legal, and legal. Source: SF Planning business planner (Choose Search by Business / Retail Sales and Service / General Retail / First floor / Yes is a chain)

Where formula retail is illegal, somewhat legal, and legal. Source: SF Planning business planner (Choose Search by Business / Retail Sales and Service / General Retail / First floor / Yes is a chain)

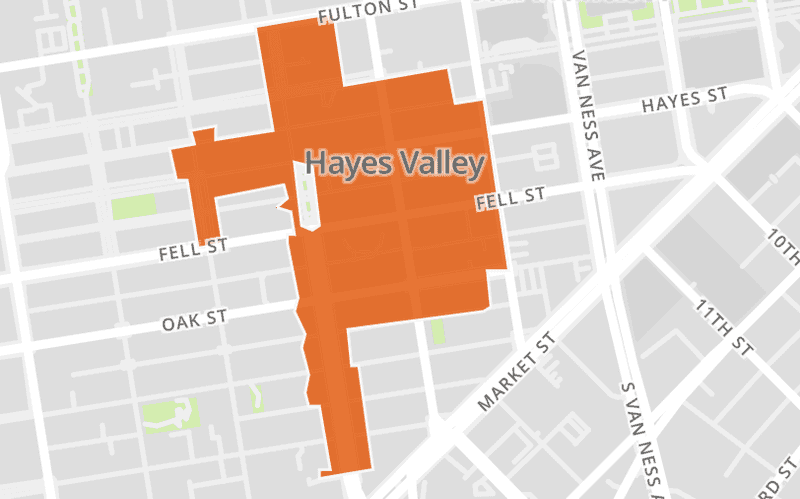

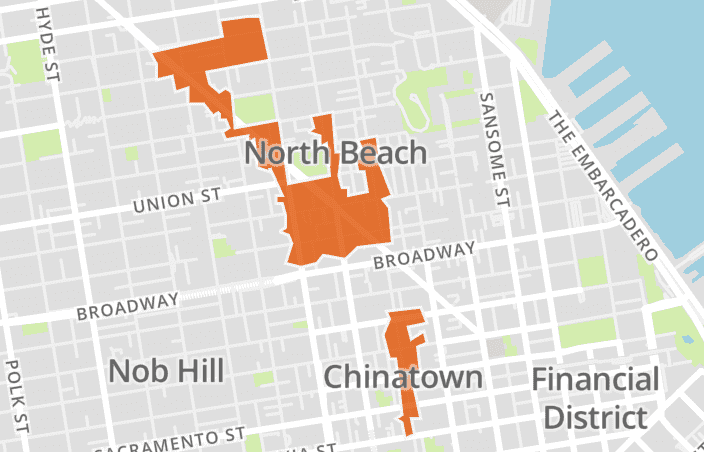

Besides residential areas, formula retail is outright banned in some commercial areas, too: several blocks of North Beach, Chinatown, and Hayes Valley.

Commercially zoned areas where chain stores are entirely banned (source: SF Zoning Data)

The law’s stated intent was to “protect San Francisco’s vibrant small business sector and create a supportive environment for new small business innovations” by preventing large, cookie-cutter chains from overrunning local commercial corridors.

In practice, though, San Francisco’s formula retail controls have hurt our city, our wallets, and our recovery from COVID. What was pitched as "protecting neighborhood character" has instead mostly protected vacant storefronts.

If Starbucks is banned, how come there are so many?

Great question! Let's clear this up first.

Since 2014, when the bans were fully implemented, San Francisco has approved 97.6% of all applicants. And since Jan 1, 2020, 100% have been approved.

It's a ban that doesn't actually stop anything, so what does it do? Simple: according to a study by Maven Commercial, on average it adds 7-8 months of delays and up to $80,000 to opening a new store. Though many retailers spend much more and take years to win approval, many give up along the way, and many more don't even bother trying. It's a cost and a delay that a growing local business simply can't afford.

Who Gets Hurt?

While the formula retail law was meant to help small businesses, it can actually hurt them once they become successful and open more locations. Here are just three recent examples of some much-loved San Francisco businesses who got hurt.

El Farolito, a family-owned taqueria founded in the Mission found out in 2021 that it was illegal to open a new store in North Beach, which has a complete ban on chain stores. But after about a year fighting City Hall, they managed to get some special "help" from Supervisor Aaron Peskin. He pointed out that they could exploit a loophole in the very law Peskin helped pass: rename and change the signs at some of their other stores outside of SF. San Francisco added a year and tens of thousands of dollars in legal fees all to change nothing. We're left wondering - who did this process help? The lawyers and consultants, apparently.

Then there's Ike's, the famous SF sandwich shop. Ike Shehadeh opened his first Ike’s in the Castro in 2007, but as his sandwich empire expanded to dozens of stores across California, he found San Francisco’s regulations choking his growth. It ultimately took two years to get permits to open a second San Francisco location. “If it wasn’t for the city, I could have opened it in 60 days,” Ike says, noting that an Oakland location was approved and built in two months. He told SF Gate that the system favors giant corporate chains over local entrepreneurs, making it so only "brands like Starbucks or McDonald's can withstand a year of rent without generating revenue” during permitting.

The San Francisco Soup Company (now Ladle & Leaf), once had 20 Bay Area locations and found the chain-store laws kept them out of certain SF neighborhoods. “It is completely unreasonable that homegrown businesses are not able to expand in this city,” she told The Chronicle. City officials on the Small Business Commission echoed these concerns, arguing the law "doesn’t make sense if it unwittingly makes it difficult for homegrown businesses” to grow.

In effect, the formula retail restrictions punish successful small businesses, rather than protect them.

Storefront Vacancies and Economic Impact

According to an analysis by Cushman & Wakefield, a commercial real estate firm, citywide retail vacancies reached 7.6% in Q1 2025, with some areas far higher. For instance, Union Square is at 22% vacancy, and Van Ness Avenue now has over 50% of its storefronts vacant on a 23-block stretch.

Are the formula retail restrictions to blame? Let's take a look at some objective economic studies. A 2014 study by the SF Office of Economic Analysis certainly indicates they aren't helping (emphasis added):

In [neighborhoods at risk of commercial decline due to blight conditions], policies that discourage formula retail tenants could have negative consequences on the surrounding neighborhood and the city's economy.

- Expanding Formula Retail Controls Economic Impact Report, Office of Economic Analysis, p. 17

And another 2014 study by Economic Strategies, commissioned by the SF Planning Department, found a similar negative impact:

Expanding the application of formula retail controls to other types of land uses could affect a significant number of businesses considering new locations in San Francisco, and make it more challenging to fill vacant storefronts in some neighborhood commercial districts.

- San Francisco Formula Retail Economic Analysis report, p. 9

There's even evidence that allowing formula retail helps nearby small businesses and neighborhoods struggling with commercial decline and vacancy:

[A] formula retailer that serves as an anchor and draws new customers to a revitalizing neighborhood commercial district can have a positive effect on other retailers in the district, and potentially lead to increased sales and rents. [...] In the Ocean Avenue Neighborhood Commercial Transit District, for example, a new Whole Foods has attracted new customers and contributed to efforts to revitalize the area.

- San Francisco Formula Retail Economic Analysis report, p. 6

For customers formula retailers typically offer lower price points. While some may prefer "shopping local," others may care more about sticking to an ever-tightening budget. Formula retailers help consumers keep more money in their pocket, which they can either save or spend at more local businesses.

]he OEA's research suggests that prices at non-formula retailers are 17% higher than they are at formula retailers.

This price difference means that, even though policies that effectively divert spending to non-formula retailers do lead to higher levels of spending on local factors of production such as business suppliers, consumers that shift their purchases to non-formula retailers will have less to spend at other businesses.

[...] the economic cost of higher prices on local consumers outweighs the potential benefit of greater local spending by non-formula retailers, and the net local spending impact is somewhat negative.

- Expanding Formula Retail Controls: Economic Impact Report, Office of Economic Analysis, p. 25

Reforms

It's clear that San Francisco’s chain store restrictions have contributed to a glut of vacant storefronts and high costs for retailers. A storefront can sit empty for months or years while a tenant navigates the process, generating no jobs, no foot traffic, and no tax revenue for the city. So how can we fix it?

There are already two proposals moving through the Board of Supervisors.

In January 2025, Supervisors Stephen Sherrill and Danny Sauter introduced a repeal of the formula retail ban for the Van Ness corridor, which has a roughly 50% vacancy rate and large footprints perfect for big retailers. The bill was co-sponsored by Supervisors Bilal Mahmood, Myrna Melgar, Matt Dorsey, Rafael Mandelman, and was passed unanimously by all Supervisors.

Supervisor Myrna Melgar has introduced legislation that would allow formula retailers to participate in the "Community Business Priority Processing Program," with the intention of helping them navigate the process faster. It's co-sponsored by Supervisor Danny Sauter and Mayor Lurie. At the time of writing, no hearing has yet taken place. Supervisor Melgar is reportedly looking into exempting like-for-like replacements of formula retailers (for example, if a Safeway would be replaced with a Lucky).

We're very thankful for Supervisor Sherrill and Sauter's bill to exempt the struggling Van Ness corridor, but we don’t believe it goes far enough – we'd like to see this applied citywide. GrowSF polling indicates a big appetite for reform: 51% of San Franciscans want to raise the limit from 11 stores, and 24% want to repeal the limit entirely, while just 16% want it to remain as-is.

Our recommendation for the Board of Supervisors is to do one or more of the following:

- Fully repeal the Formula Retail Controls, since no positive impact has been gained from the limits

- a) Increase the limit from 11 worldwide stores to 1000, or

b) Change the limit from 11 worldwide to 25 in SF - Limit the definition of "formula retail" to footprints of 50,000 square feet or more (i.e. big-box retailers)

- By-right activation of long-term vacancies (ie 12 months or more vacant)

Let's get the roadblocks out of the way and help San Francisco's economy recover.

Generate a Personalized Email to the Board of Supervisors

To:

Sign up for the GrowSF Report

Our weekly roundup of news & Insights