San Francisco's retail vacancy problem

July 14, 2025

San Francisco's retail vacancy crisis is the product of our uniquely rigid planning codes, a legal requirement for almost all new buildings to include ground-floor retail space, and inflexible rules for adaptive re-use.

San Francisco is grappling with stubbornly high retail vacancies. COVID and the rise of remote work are certainly big factors in our crisis, but they're not the whole story. In fact, San Francisco's retail vacancy crisis is the product of our uniquely rigid planning codes, a legal requirement for almost all new buildings to include ground-floor retail space, and inflexible rules for adaptive re-use.

The city's rules, designed for a bygone era of retail, are actively preventing the market from adapting and repurposing these underutilized assets. We've done it to ourselves, but we can choose to undo it.

Concentrated vacancies are the real issue

Surprisingly, San Francisco's overall retail vacancy rate isn't that high. It's higher than Seattle's, but lower than New York City's. But where it really stands apart is the concentrated pockets of vacancy.

| City | Total Retail ft2 | Population | Retail ft2 per Capita | Vacancy Rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Francisco | 50.9M ft2 (Q1 25) | 827,526 (2024) | ~61.5 ft2 | 7.6% Citywide (Q1 25) 53% Van Ness (Q1 25) 22% Union Square (Q1 25) |

| San Francisco (daytime) | 1,100,000 (2019) | ~46.2 ft2 | ||

| Seattle | 65.9M ft2 (Q1 21) | 780,995 (2024) | ~82.6 ft2 | 3.2% Citywide (Q1 25) ~13% Central business district (q2 2024) ~20% Downtown neighborhoods (q2 2024) |

| New York City | 273M ft2 (2017) | 8,478,072 (2024) | ~32.2 ft2 | 11.04% Citywide (99% of pre-COVID) 14.2% Manhattan 11.9% Brooklyn 8.7% Queens 8.2% Bronx (better than pre-COVID) 8.6% Staten Island (better than pre-COVID) (Q1 25) |

| Manhattan | 100M ft2 (2017) | 1,660,000 (2024) | ~60.2 ft2 | 13.5% (lowest in 10 years) 14.5% flatiron/union square <10% Upper East Side <10% Upper West Side 24% Meatpacking 19% Lower Manhattan (Q1 25) |

| Manhattan (daytime) | 4,000,000 (2012) | ~25 ft2 |

Compared with New York City, where retail vacancy rates are just above pre-COVID rates, we're actually doing better! But vacancy rates in certain neighborhoods tell a different story. Union Square and the Van Ness corridor have staggering retail vacancy levels: 22% and 53% respectively. Unfortunately, there is no public retail vacancy data for Soma, Fisherman's Wharf, or Mission Street, but anecdotal reports indicate higher-than-city-average retail vacancy rates there, as well.

There's no clear relationship between the retail space per capita and the citywide vacancy rate, but the neighborhoods in San Francisco which are struggling the most are also the hardest hit from a lack of commuters and tourists. In these neighborhoods the market suddenly has a mismatch between supply of retail and demand for it. And, though some activists have claimed that "supply and demand don't apply to San Francisco," we really can't escape this fundamental rule of economics.

So if the supply is too big for the demand, why hasn't the market adjusted and repurposed the vacant spaces? Well, like so many things in San Francisco, that's largely illegal. Let's dig in.

Mis-sized market, mandatory expansion

Despite a growing population (about 21% growth between 2010 and 2020) and a strong local economy, Seattle has actually been shrinking its retail supply. In the past four years alone, about 1.5 million square feet of retail in Seattle was removed from the market and redeveloped into new mixed-use spaces. This is a far cry from San Francisco, where retail space has been added year-after-year despite sluggish demand.

You've probably noticed large empty spaces on the ground floor of new residential buildings. And you've probably noticed that they've sat vacant ever since that building was finished. But you probably didn't know that the developers don't care if they fill it. In fact, they already priced the vacant space into the cost of the building, and it's all due to San Francisco's mandatory ground-floor retail law.

Urban planners have long championed mandatory ground-floor retail as a key tool for creating active streets. In the 1990s, many U.S. cities started to require retail, dining, or other high-foot-traffic uses on the ground floor in order to prevent sidewalks from becoming dead zones. The idea was that retail would attract people, bringing more business activity to the city, and making neighborhoods feel more lively. In fairness, this did seem to work for a while. And in the past couple years, planners have started to change their tune.

"In today’s white-hot San Francisco, ground-floor retail has pretty good prospects, and businesses can and do make use of all kinds of spaces, from the 12- foot frontages along Hayes Street to ActivSpace on 18th and Treat Streets, which houses a thriving café in just 99 square feet. But elsewhere, ground floor space often sits empty, a planner’s aspiration that never bore fruit. [...] The cost of empty retail space is simply folded into the cost of the space upstairs."" - Designing at Ground Floor, SPUR, 2014

San Francisco's ground-floor retail requirement first appeared in the 1985 Downtown Plan, which mandated that all "C-3" commercial areas include ground-floor retail. Its explicit goal was to bring more office and retail space into the city, which admittedly made a lot of sense at the time.

"The principal section of the Downtown Plan is the Space for Commerce chapter. [...] this key section of the Plan called for various rezonings to encourage street-level activity by requiring ground floor retail…"

25 Years - Downtown Plan Monitoring Report 1985 - 2009

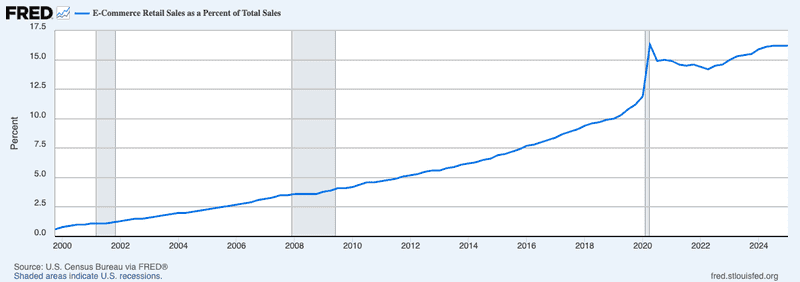

But what the Downtown Plan couldn't see coming was the rise of e-commerce.

E-commerce continues to make up a growing share of all retail sales. Source: FRED

E-commerce continues to make up a growing share of all retail sales. Source: FRED

In 2008, the Eastern Neighborhoods Plan extended the ground-floor retail mandate to new corridors. By this time it was becoming apparent to technologists that e-commerce would continue to grow at a rapid pace. But despite being known for our tech industry, policy leaders did not adjust to the new normal. It took a global pandemic and record-high vacancies for elected officials to realize we made rules for a reality that no longer existed.

Despite the softening retail market, the residential market stayed hot. So property developers still needed to build housing, even when ground-floor retail space was a mandatory, undesirable component. Developers aren't dumb – they knew they would struggle to find a retail tenant but also knew they couldn't change the existing laws. So they found the only way to make their buildings work: put the minimum amount of cost and effort into the mandatory retail space, write it off as a deadweight loss, and focus on the actual tenants instead.

But the boom times are over and now we have a retail supply that vastly outstrips demand, yet developers are still required to build a space that everyone knows won't be used. It makes buildings harder to finance and thus more expensive to build.

Change is hard, expensive, and sometimes illegal

Building owners struggling to fill a retail storefront have limited options, and their best options are even illegal in some parts of the city. San Francisco has strict rules about what type of business is or isn't allowed in any particular space, and no conversion of use is guaranteed by law.

In high-vacancy retail corridors, our laws often require that retail businesses fill these vacant spots, rather than let it be something else.

In North Beach, businesses are subjected to the North Beach Special Use District, which makes it illegal to convert a retail storefront into things like a restaurant, bar, coffee shop, church, school, or residence. Some office spaces, like a dentist or accounting firm, or even a real estate office would be allowed, but the law stipulates that new uses must promote "active commercial uses" – i.e. regular foot traffic… even if there's no current foot traffic due to a vacancy.

Fun fact: the North Beach Special Use District zoning prevents any new restaurant space from being created! A restaurant is only allowed to fill a spot vacated by another restaurant or bar. Bars can only replace bars.

Not every neighborhood is as conservative and change-averse as North Beach, though. The Van Ness corridor, which has 53% retail vacancy, is more permissive (and even more so now that restrictions on formula retail have been loosened), though converting vacant retail space into office space is still illegal. So why does this corridor have the highest vacancy rate in the city? There's no clear answer, but there are a few plausible theories: the cost of converting a space to a new use (think installing a kitchen in a former clothing store), alternative non-retail uses (like general office space) are illegal, and, frankly, that the corridor just isn't nice.

We can help ameliorate these issues by lowering the cost of upgrades via grants and limited tax breaks, changing the zoning rules to be even more permissive, and trying to make the street generally nicer. Van Ness has a great, high-speed dedicated bus lane, so let's make the road nicer for people once they get off the bus. How about some trees? How about cleaner sidewalks?

Make change legal again, and help make it happen

Let's consider a future where brick-and-mortar retail doesn't rebound. It's a declining market, consumer preference for online shopping has been growing steadily year-after-year, commuters may not come back anytime soon, and tourists are no longer coming to San Francisco to shop. Let it go.

We have three simple policy proposals to fix our retail vacancy problems:

- Stop requiring new buildings to build ground-floor retail

- Let vacant spaces become something else, only restricting high-nuisance or polluting uses

- Issue grants, or give tax credits, to building owners or entrepreneurs who pay to improve their spaces

Repealing the ground-floor retail requirement is simple – just repeal SF Planning Code Section 145.5. It will immediately make new buildings more affordable to build, and stop growing the oversupply of retail space. San Diego is already trying this by temporarily repealing their own ground-floor retail requirement, and they started before the COVID retail slump.

Letting vacant spaces transform into other uses can be fairly straightforward. Lawmakers should go broad and change how our zoning codes handle allowable uses. We should make our laws permissive by default, rather than exclusive, and only restrict uses known to be a nuisance, rather than be prescriptive about what is allowed. For example, in late 2019 California lawmakers passed AB68, which allowed vacant ground-floor retail spaces in multifamily residential buildings to be converted into housing. But four years later, nobody has done it in San Francisco. Lawmakers shouldn't guess what developers or consumers want – they should let them be creative, instead.

Finally, grants and tax credits for improvements on commercial space would make it more affordable and less risky to try out a new business type in an existing vacant space. This is already being tried out in Washington, D.C., though it was only enacted a few months ago so it's too early to judge its performance. San Francisco has a "Vibrancy Loan Fund" that offers low-interest (4%) loans to small businesses moving into ground-floor retail spaces, which launched in 2024 under Mayor Breed. We are not aware of any analysis on the success of this new program, yet, but we hope it works!

The Office to Anything program, officially known as the Central Washington Activation Projects Temporary Tax Abatement, will support the repositioning of outdated and obsolete office space into new retail spaces, hotels, world-class office space, restaurants, and other non-residential uses by offering a 15-year temporary property tax freeze.

- The Deputy Mayor’s Office of Planning and Economic Development, Washington, D.C.

We should reward owners taking risks on new businesses, and help them out if they fail. We can use this same structure to incentivize converting San Francisco's huge supply of class C office space into more desirable space, hopefully reactivating vacant offices and bringing more foot traffic downtown.

While the causes of rising retail vacancies may be myriad and complex, the solutions need not be.

Addendum: Nobody wants to lose money

We often hear that landlords purposefully hold properties off the market, waiting for a tenant at the price they want. We found that claim dubious, but upon doing some research we happened upon a scenario where it can make sense. Here's that research, which was too complex for the main article:

Like any rational person, property owners and landlords would rather make money than lose money. So why do landlords seem content to sit on a vacancy rather than rent it out for less than they'd prefer? It's a great question with a complicated answer.

In our conversations with developers, landlords, small business owners, and entrepreneurs, we've identified a few plausible reasons, but one stands out: building owners can actually lose more money by leasing at below market rates than by keeping a space vacant. It all comes down to how commercial real estate finance works.

You need to know two key things about commercial real estate finance.

First, how a building is valued:

If you've shopped for a home in San Francisco, you're probably familiar with "comps" – that is, what comparable homes have sold for. This approach to valuing a property is not typically used for an income-generating property like commercial real estate. Instead, the value of a building is determined by its projected return on investment.

The value of a commercial building is determined by its Net Operating Income (NOI) and the Capitalization Rate (cap rate). The cap rate is, roughly, the expected rate of return for the investment you make in a building.

The value of a building with a NOI of $1 million and a cap rate of 5% is $20 million:

$20,000,000 = $1,000,000 / 0.05

You can also think of this like you're capturing 5% of the building's total value per year. The typical cap rates are pretty standard in an industry, and it'd be difficult to find a mortgage for a building when using a non-standard cap rate.

Second, how a commercial mortgage is paid:

Rather than a 30-year mortgage typical of a home, where you make a fixed payment every month for 30 years, a commercial mortgage will require the entire balance of the loan to be paid off within 5 to 10 years (this is called a balloon payment). Typically, this is done by refinancing the property, which gets owners in trouble in struggling markets.

A commercial mortgage typically requires a loan-to-value (LTV) ratio between 60% and 80%. Meaning if you want to buy this $20M building with a 70% LTV, you need to put down $6M and the loan would be for $14M.

Now, here's how a vacancy is worth more than a below market lease:

(The values below were calculated with the help of this commercial mortgage calculator.)

Say you bought this building in 2018 for $20M, with $6M down and a mortgage for $14M at 5% interest. Each month you earn $83k in rent ($1M / 12 months) and pay $75k on the mortgage, so you net about $100k per year. The bank is happy, and they are looking forward to their balloon payment of approximately $11.4M in 2028. But there's a problem: your tenant stopped paying rent during COVID and vacated in 2021, and your space has sat empty since then. You have a real NOI of $0, and every month you're losing $75k. It's 2025 and instead of earning $700k, you've lost $4.5M and you're not sure you'll see your $6M down payment again.

Let's say you decide to sell. Interest rates are up now, so the buyer needs a 10% cap rate, and based on your projected $1M NOI the building is now only worth $10M. You sign the papers and offload your asset, but you owed the bank about $13M. So in addition to the $6M you put down and the $4.5M you had lost to mortgage payments, you had to pay the bank another $3M. Congrats, you lost $10.5M.

But let's say you found a tenant and, instead of charging them the market rate for your space, you lock in a 7 year lease below market, putting you at an $700k NOI, or about $58k per month (a net loss of $17,000 per month, or $200k per year, or $600k for the next three years of your loan). You'd think this would be better because some income is better than no income, right? Wrong. When you have to refinance the building in 2028, interest rates have gone up, now requiring a 10% cap rate. Your $700k NOI means your building is only worth $7M. So you get a new loan for the full $7M, but your first bank still needs its money, and you owe $11.3 million. So you've already lost $600k and now you need to find another $4.3 million. Oops.

Ok, both of those options lose you a lot of money. So instead of that, you want to refinance your loan, keep the building, and hopefully find a tenant once the market recovers. If your space stays vacant until it's time to refinance, you can still make a somewhat credible argument that your building still demands the market rate, you just haven't found the right tenant. Your balloon payment costs $11.3, so you only need a new mortgage for that much. Sure, interest rates have gone up, but with a cap rate of 10%, the building is still worth $10M and your mortgage payment is lower - just $60k per month. Yes, you still need to cough up $1.3M to cover the rest, and combined with the $2.7M you've already lost by not having a tenant, your total losses are at $4M. But hey, that's less than you would have lost in the other scenarios, and you still own a building "worth" $10M, not $7M. And who knows, maybe the market will turn around soon and you can secure a tenant that puts you at a $1.2M NOI. Maybe.

Congratulations, you've managed to lose money on property in San Francisco!

Generate a Personalized Email to the Board of Supervisors

To:

Sign up for the GrowSF Report

Our weekly roundup of news & Insights