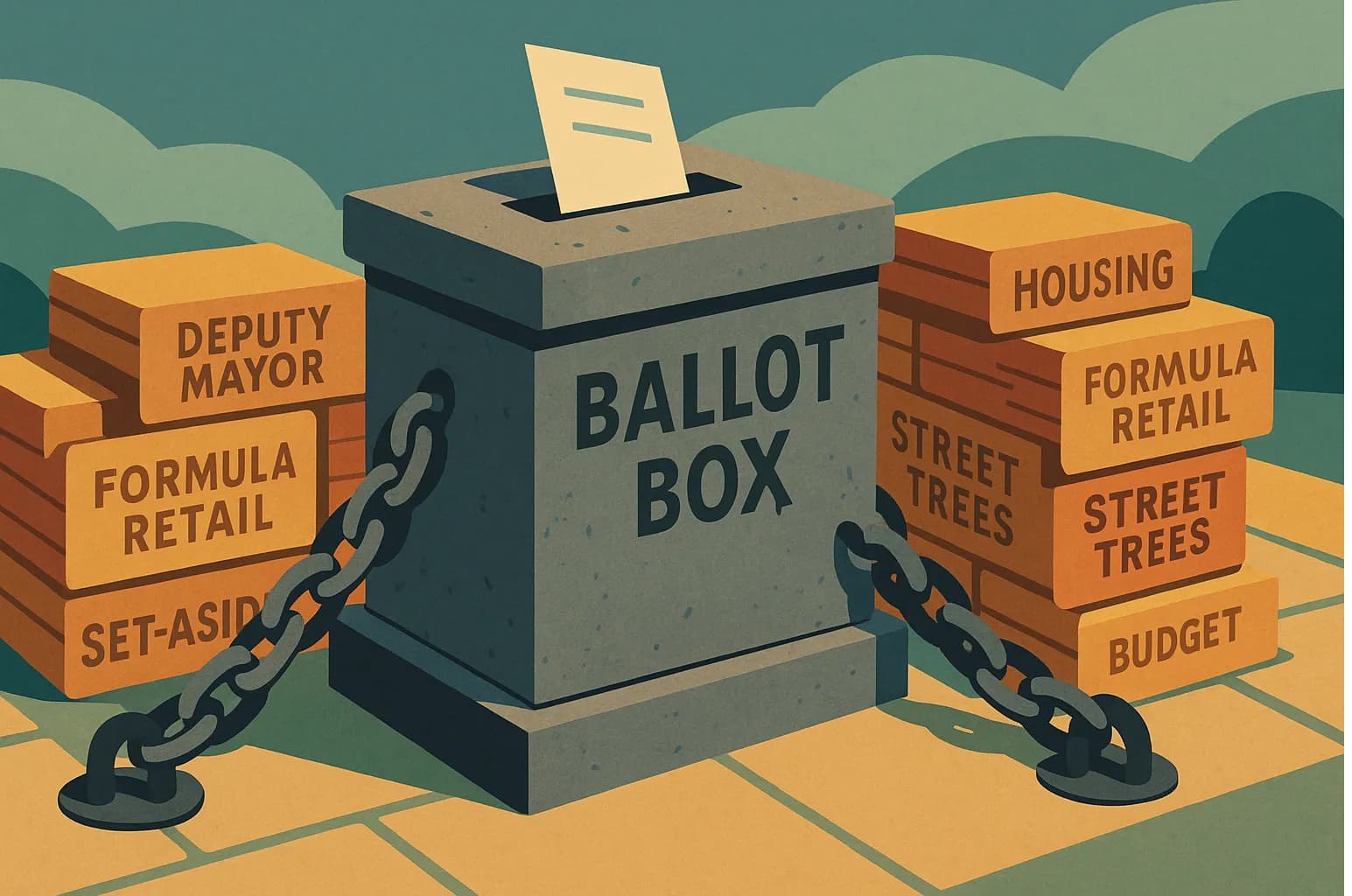

We pass a lot of ballot measures, which means a lot of laws are set in stone. San Francisco's Charter makes voter-approved measures exceptionally difficult to alter or repeal. In fact, any law adopted by voters cannot be amended, fixed, or undone by elected leaders.

This legal rule (Charter Article XIV, Section 14.101) means that policies enacted via ballot initiative are effectively permanent unless another expensive campaign is run for a citywide vote. Even minor corrections or updates to voter-adopted laws require costly ballot measures, so outdated provisions tend to linger. A recent SPUR report notes that the path of least resistance to fixing an error is usually to leave it in place or add new layers on top.

San Francisco's heavy use of direct democracy contributes to city hall rigidity. Between 2013 and 2022, San Francisco voters considered 115 local ballot measures—more than twice as many as in San Diego, the next closest California city. Notably, about 70% of those SF measures were put on the ballot by city officials themselves, which we criticized in "Too Many Ballot Measures."

In short, San Francisco's Charter and initiative process give voters immense power over policy, but at the cost of flexibility: once voted on at the ballot box, policies are virtually permanent until/unless the entire city votes again to change them.

Voter Mandates and Set-Asides Limit Budget Flexibility

Voter-mandated spending requirements (often called "baselines" or "set-asides") heavily constrain San Francisco's budget.

Between 1994 and 2022, the percent of the city's General Fund budget tied up in voter-mandated set-asides doubled—from 15% to 30%. A 2024 Civil Grand Jury report found that over 30% of the city's General Fund budget is tied up by more than 20 voter-approved spending mandates. By contrast, all other cities and counties in California combined have just 10.

These voter-adopted set-asides guarantee funding for certain programs regardless of other needs. While it may sound great to dedicate millions of dollars to maintaining street trees, when the City is facing a huge budget deficit, it'd be nice to be able to reallocate that money to fund other priorities like Muni and the police.

The San Francisco Controller's Office explains that while set-asides tend "to increase certainty regarding year to year funding levels", they also "limit the financial flexibility of elected policymakers." As more of the budget is pre-allocated by law, any necessary cuts or reallocations must come from an ever-shrinking portion of the discretionary budget.

City oversight bodies have flagged this rigidity as a growing problem. The Civil Grand Jury noted that "voter-mandated spending (set-asides) significantly affects management of the city's budget", and it urged a dedicated analysis of how to handle these constraints.

While San Francisco's myriad voter-imposed budget mandates provide certainty for certain services, collectively they force a shrinking portion of the city budget to absorb 100% of any budget deficit while limiting budget flexibility along the way.

Outdated Mandates

A recent example of structural dysfunction (and clever workaround) is San Francisco's prohibition on Deputy Mayors. In most major cities, mayors appoint deputy mayors or similar managers to coordinate broad policy areas—New York City and Los Angeles, for instance, both employ deputy mayors. San Francisco, however, banned deputy mayors with a 1991 ballot initiative: Proposition H.

The ban was driven by "anger over the high salaries of deputy mayors," but its long-term effect has been to hamstring the Mayor's Office, stymie cross-departmental coordination, and make government less effective. Rather than a team of deputy mayors overseeing clusters of departments, the Mayor was forced to rely on just their Chief of Staff.

Mayor Lurie, for his part, figured out a workaround in 2024 by creating several Policy Chiefs within the Mayor's Office to oversee key areas like housing, public safety, and economic development. But these Chiefs lack any legal authority, and the Mayor's Office still faces challenges coordinating across siloed departments and commissions.

Given that the city seems to be running much better with these Policy Chiefs in place, it's clear that the 1991 ban on deputy mayors is an outdated impediment to effective governance. But it's still the law of the land, and properly fixing it will require another expensive citywide vote.

City leaders today recognize that some well-intentioned mandates from a bygone era are now acting as impediments to good government. But meaningful reform will ultimately require asking the voters to "clean up" the charter by removing or modernizing entrenched provisions.

Good Governance Needs Flexibility, and Fewer Ballot-box Mandates

Governance works best when there's room to adapt. That's why good-government experts like SPUR urge San Francisco to "resolve issues through leadership rather than at the ballot". Voters should set broad direction and priorities, but then let the Mayor, Board of Supervisors, and city departments work out the details, and adjust on the fly as needed. We elect our leaders to problem-solve and make informed decisions. They can't do that effectively if every adjustment requires a citywide vote to undo an old mandate.

San Francisco needs to regain some flexibility in its laws. When policies prove unworkable or circumstances evolve, our officials should be able to course-correct without waiting for the next election. That doesn't mean shutting voters out, but it does mean only using the ballot box for big-picture guidance, not minute administrative rules. And that probably looks like making it hard to put ballot measures on the ballot.

Empower Elected Representatives

At the end of the day, we elect our Mayor and Supervisors to govern, and we should let them do it. That means shifting away from direct democracy at the ballot box as the default and back toward representative democracy.

If the Mayor and Board are empowered to actually govern, and can be expected to negotiate solutions instead of waging ballot campaigns against each other,voters can then judge them on their performance. We'll know whom to credit or blame. Right now, responsibility is often muddled: was it the voters' fault or the officials' fault that something went wrong?

Returning decision-making power to our elected officials will improve the City's governance and clarify accountability. And if we don't like the job they're doing, we can vote them out, rather than trying to micro-manage the City via propositions.

Generate a Personalized Email to the Board of Supervisors

To:

Sign up for the GrowSF Report

Our weekly roundup of news & Insights